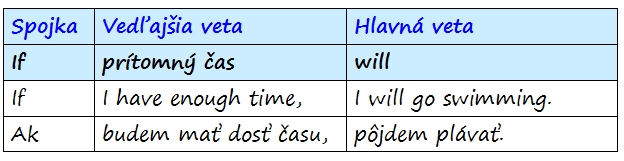

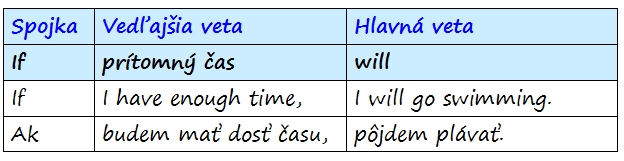

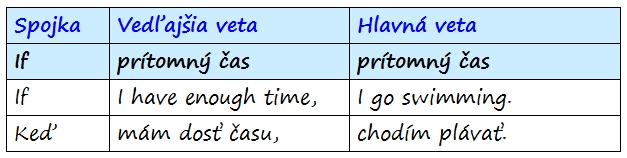

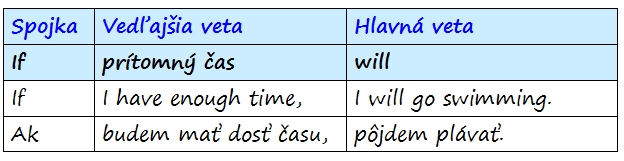

Po IF budúcnosť nevyjadrujeme pomocou budúceho času, ale budúci význam tu vytvára PRESENT SIMPLE. Existujú však niektoré špecifické situácie, kedy sa WILL môže použiť aj po IF. Na túto problematiku sa však pozrieme v inom článku.

- If I

will have enough time, I will go swimming.

- If you don’t hurry, you‘ll miss the bus.

- If we leave at eight o’clock, we will be there by half past nine.

Namiesto PRESENT SIMPLE môžete vo vete po IF (vedľajšej) použiť PRESENT CONTINUOUS (prítomný priebehový), či PRESENT PERFECT (predprítomný čas).

- If you have finished eating, we will go for a walk.

- If we are working till ten, we will have to go home by bus at eleven.

Namiesto WILL môžete v MAIN CLAUSE (hlavnej vete) použiť MODAL VERBS (modálne slovesá) ako napr. CAN / MAY / MIGHT / MUST / SHOULD alebo napr. IMPERATIVE (rozkazovací spôsob).

- If you have finished eating, we can go out. – Ak doješ, môžeme ísť von.

- If you go shopping, call me. – Ak pojdeš nakupovať, zavolaj mi.

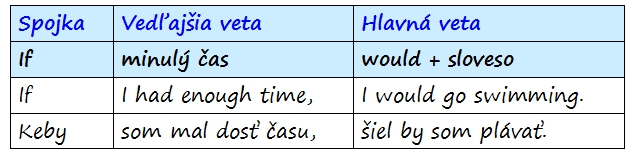

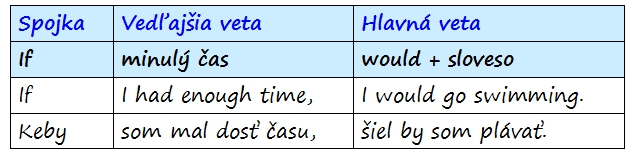

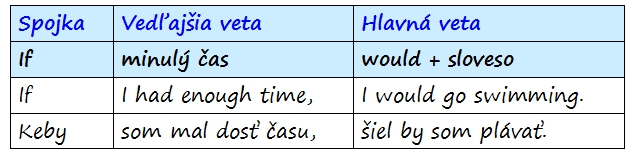

Druhý kondicionál (second conditional)

Druhý kondicionál používame vtedy, ak hovoríme o situáciach, ktoré sú hypotetické, imaginárne, či vymyslené.

Tieto situácie sa týkajú prítomnosti, poprípade budúcnosti.

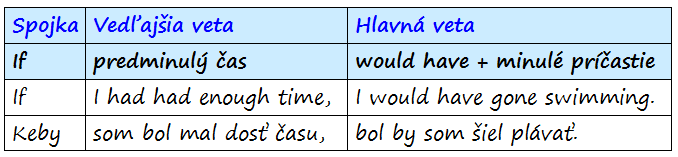

|

- Keby som mal dosť času, šiel by som plávať. → Čo by sa stalo, keby bola splnená podmienka “mať dosť času? (hypotetická situácia – čo by bolo keby?) – šiel by som plávať ⇒ podmienka však splnená nie je (nemám dosť času), a preto mi neostáva nič iné, len na plávanie zabudnúť.

Druhý kondicionál tvoríme nasledovne:

|

IF + past simple + would

Vedľajšia veta (if-clause) obsahuje minulý čas a hlavná veta (main clause) obsahuje WOULD + sloveso v základnom tvare.

|

- If I had a million dollars, I‘d buy a car. - MINULÝ ČAS tu naznačuje nereálnu podmienku. “If I had a million dollars” znamená, že v skutočnosti toto množstvo peňazí nemám, iba si ho predstavujem.

- If I won the lottery, I would travel the world.

- If you missed the train, you would have to go home on foot. - MINULÝ ČAS tu vyjadruje imaginárny (vymyslený) budúci dej – zmeškanie autobusu.

Niekoľko príkladov druhého kondicionálu si ukážeme aj na piesní od Erica Claptona – Tears In Heaven:

Would you know my name

If I saw you in heaven?

Would you feel the same

If I saw you in heaven?

I must be strong and carry on

Cause I know I don’t belong here in heaven…

Namiesto PAST SIMPLE môžete vo vete po IF (vedľajšej) použiť PAST CONTINUOUS (minulý priebehový), či COULD (= vedel/mohol by).

- If it was not raining, we would go out.

- If I could sing, I would, but I can’t.

Namiesto WOULD môžete v MAIN CLAUSE (hlavnej vete) použiť MODAL VERBS (modálne slovesá) ako napr. COULD / MIGHT.

- If I had a million dollars, I could go abroad. – Keby som mal milión dolárov, mohol by som ísť do zahraničia.

- If I had a million dollars, I might go abroad. – Keby som mal milión dolárov, možno by som šiel do zahraničia. – MIGHT vyjadruje vo vete menšiu istotu

Sloveso BE v tvare WERE môžeme použiť i pri osobách I / HE / SHE / IT.

- If I were you, I would help her. (Keby som bol tebou – Keby som bol na tvojom mieste, pomohol by som jej.) - IF I WERE YOU je ustálená väzba.

- If he was / were so mean, he would …

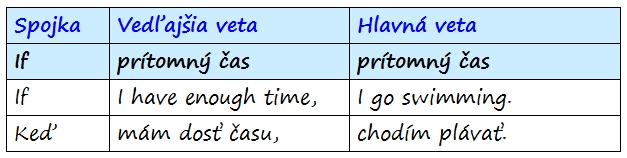

Porovnajte prvý kondicionál a druhý:

- Prvý kondicionál: If I have enough time, I will go swimming. - Ak budem mať dosť času, pôjdem plávať. – ČO BUDE AK → reálnejšia podmienka, otvorená podmienka – môže byť splnená, možno budem mať dosť času / možno nie

- Druhý kondicionál: If I had enough time, I would go swimming. - Keby som mal dosť času, šiel by som plávať. – ČO BY BOLO KEBY → hypotetickejšia situácia, vzdialenejšia od reality. K naplneniu deja nedôjde, lebo podmienka nie je splnená.

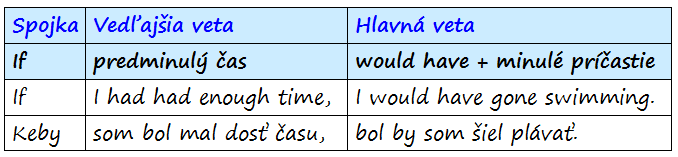

Tretí kondicionál (third conditional)

Tretí kondicionál používame výlučne vtedy, ak hovoríme o minulosti. Situácie sú imaginárne / hypotetické.

Podmienka je nereálna a keďže sa deje týkajú minulosti, podmienka sa splniť už nedá.

Tretí kondicionál sa teda týka dejov, ktoré v minulosti prebehli / neprebehli.

|

- Keby som bol mal dosť času, bol by som šiel plávať. → Čo by sa bolo bývalo stalo, keby bola bývala splnená podmienka “mať dosť času”? (hypotetická situácia v minulosti) – bol by som šiel plávať – podmienka však splnená nebola (nemal som dosť času) a preto som plávať nešiel.

Tretí kondicionál tvoríme nasledovne:

|

IF + past perfect + would have done

Vedľajšia veta (if-clause) obsahuje predminulý čas a hlavná veta (main clause) obsahuje WOULD HAVE + minulé príčastie slovesa.

|

- If we had taken a taxi, we wouldn’t have missed the plane. - PAST PERFECT uvádza nerálnu / hypotetickú podmienku v minulosti. “If we had taken a taxi” naznačuje, že sme si taxík nevzali a tak sme lietadlo nestihli.

- If I had been ill, I would have seen a doctor.

Namiesto WOULD HAVE + minulé príčastie môžete v MAIN CLAUSE (hlavnej vete) použiť MODAL VERBS (modálne slovesá) ako napr. COULD HAVE + minulé príčastie (bol by dokázal) / MIGHT HAVE + minulé príčastie (MIGHT vyjadruje vo vete menšiu istotu)

- If I had been ill, I might have seen a doctor. – Keby som bol býval chorý, možno by som bol šiel k doktorovi.)

Zhrnutie:

Nultý kondicionál (zero conditional)

- čo je, ak … (prítomnosť – všeobecné pravdy)

Prvý kondicionál (first conditional)

- čo bude, ak … (budúcnosť – reálna podmienka)

Druhý kondicionál (second conditional)

- čo by bolo, keby … (prítomnosť – hypotetická podmienka)

Tretí kondicionál (third conditional)

- čo by bolo bývalo, keby … (minulosť – hypotetická podmienka)

22nd NOVEMBER

https://www.englisch-hilfen.de/en/exercises_list/if.htm

READ AND LEARN

27_education_uk_usa_cr.pdf

18_CARD_education.pdf

YES!book 56/TASK F

I am studying at Secondary School of Printing and Publishing. Now I am in the 2nd, 3rd, 4th class. This school prepares students for different professions in the fields of printing and publishing. A lot of its graduates start to work in publishing companies, printing houses, advertising agencies or graphic studios as web-designers (návrhári webových stránok), digital media designers (dizajnér digitálnych médií), pre-press technicians (technickí pracovníci zodpovední za prípravu tlače), printing machinery operators (operátori tlače), digital printing operators (operátori digitálnej tlače), and bookbinders (kníhviazači). When I graduate I would like to work in___________ as

8th October

English file - Vocabulary bank 161- EDUCATION Learn vocabulary with the correct pronunciation.

Revise Vocab bank 160, WB 40-41

9th October

You are learning the topic Mass MEDIA YES!book pages 146-151. To get more information learn the text IV.GMB KAJ tab on edupage. Task C/ written homework.

25th October

Revise modals of deduction and Vocabulary Bank page 160 The body (the whole page pls)

24th October

Be prepared for KAJ and learn the text from your tab and follow the instruction written there.

PRACTISE ENGLISH TENSES

http://www.englishguide.sk/test-english-tenses-review-1/

Active / Passive Overview

|

|

Active

|

Passive

|

|

Simple Present

|

Once a week, Tom cleans the house.

|

Once a week, the house is cleaned by Tom.

|

|

Present Continuous

|

Right now, Sarah is writing the letter.

|

Right now, the letter is being written by Sarah.

|

|

Simple Past

|

Sam repaired the car.

|

The car was repaired by Sam.

|

|

Past Continuous

|

The salesman was helping the customer when the thief came into the store.

|

The customer was being helped by the salesman when the thief came into the store.

|

|

Present Perfect

|

Many tourists have visited that castle.

|

That castle has been visited by many tourists.

|

|

Present Perfect Continuous

|

Recently, John has been doing the work.

|

Recently, the work has been being done by John.

|

|

Past Perfect

|

George had repaired many cars before he received his mechanic's license.

|

Many cars had been repaired by George before he received his mechanic's license.

|

|

Past Perfect Continuous

|

Chef Jones had been preparing the restaurant's fantastic dinners for two years before he moved to Paris.

|

The restaurant's fantastic dinners had been being prepared by Chef Jones for two years before he moved to Paris.

|

|

Simple Future

will

|

Someone will finish the work by 5:00 PM.

|

The work will be finished by 5:00 PM.

|

|

Simple Future

be going to

|

Sally is going to make a beautiful dinner tonight.

|

A beautiful dinner is going to be made by Sally tonight.

|

|

Future Continuous

will

|

At 8:00 PM tonight, John will be washing the dishes.

|

At 8:00 PM tonight, the dishes will be being washed by John.

|

|

Future Continuous

be going to

|

At 8:00 PM tonight, John is going to be washing the dishes.

|

At 8:00 PM tonight, the dishes are going to be being washed by John.

|

|

Future Perfect

will

|

They will have completed the project before the deadline.

|

The project will have been completed before the deadline.

|

|

Future Perfect

be going to

|

They are going to have completed the project before the deadline.

|

The project is going to have been completed before the deadline.

|

|

Future Perfect Continuous

will

|

The famous artist will have been painting the mural for over six months by the time it is finished.

|

The mural will have been being painted by the famous artist for over six months by the time it is finished.

|

|

Future Perfect Continuous

be going to

|

The famous artist is going to have been painting the mural for over six months by the time it is finished.

|

The mural is going to have been being painted by the famous artist for over six months by the time it is finished.

|

|

Used to

|

Jerry used to pay the bills.

|

The bills used to be paid by Jerry.

|

|

Would Always

|

My mother would always make the pies.

|

The pies would always be made by my mother.

|

|

Future in the Past

Would

|

I knew John would finish the work by 5:00 PM.

|

I knew the work would be finished by 5:00 PM.

|

|

Future in the Past

Was Going to

|

I thought Sally was going to make a beautiful dinner tonight.

|

I thought a beautiful dinner was going to be made by Sally tonight.

|

12th October

ENGLISH FILE B + YES!BOOK

Read and learn Towns and Places, the 17th topic in Yes!book/ in scanned Yes!book yes-b1.pdf.

22_TOWNS_AND_PLACES.ppt

20.Towns_and_places.docx

those who were absent - WB p. 37-38, Vocabulary bank 159

WRITING - a film review p. 117, read it, fill in the gaps and hand in a similar one reviewing a different movie of your own choice.

10th October

SB Grammar Bank 142 / Passives ex. a, b

6th October

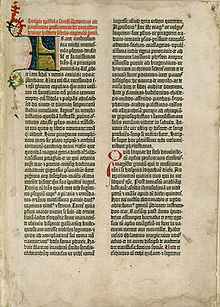

Learn about history of the book, Parts of the book (front matter, body matter and end matter) + Gutenberg+YES!book the topic 24 The Book - The Friend of People

A HISTORY OF THE BOOK

Beginnings of the Book

Sumerians

Writing with words was invented by the Sumerians about five thousand years ago (c.3100 BC). Sumer was located in what is now Southern Iraq.

. They wrote, e.g. on stone,

2. then they developed baked clay tablets, which can be regarded as the first books.

Egyptians

These were soon followed by

3. the papyrus rolls of the Egyptians, made from a plant native only to the Nile Valley. From around 500 BC the papyrus roll became dominant, although clay tablets survived for another five hundred years or so.

4. Wooden tablets followed. Students, merchants and others could write on the wax, then erase their markings and reuse the surface. These tablets could be connected in groups, which formed a model for the later codex book.

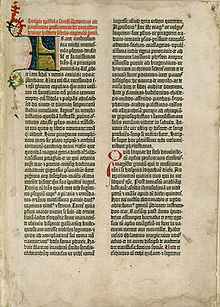

5. The Codex/bound book

The traditional modern form of the book is called the codex. It has multiple separate leaves of pages, bound between protective covers.

This format has been with us for about nineteen hundred years (from around the second century AD). The codex book (plural = codices) has survived so long because it has many unique advantages.

The first codex books used as the writing surface:

· papyrus (papyrus plant), later

· parchment (made from animal- goat and calfskin, it was more suitable for the new format)

By the 7th century AD, parchment had almost replaced papyrus altogether in Europe and the Middle East, and remained the preferred medium in Europe for about 800 years longer.

From paper to digital books

Made of bark and hemp

Paper was invented in China as early as 105 AD, and was at first prepared from bark and hemp. This paper developed to a high standard, and paper-making later spread to Japan (c.610 AD), and then to the Arab world along the Silk Road, via Samarkand in Central Asia. Pre-Columbian American civilizations also produced a more primitive bark paper from an unknown date.

Made of flax and hemp

The Arabs introduced paper into Europe via Spain; around 1276 AD into Italy and in 1495 into England. One reason for this slow advance was that European-style paper, made usually from flax and hemp, was at first inferior to parchment, especially for illustrations. So until it was improved, paper was not very suitable for the style of illustrated manuscript common in the West.

baked clay tablet papyrus plant Chinese block printing,

medieval illustrated manuscript Gutenberg printing press

rotary press first modern e-reader device (the Rocket eBook)

Digital printing

E-book

Audio-book

TASK

Write the missing words in the picture and sentences below. Choose from the following:

|

acknowledgements

|

contents

|

illustrations

|

|

appendix

|

cover

|

index

|

|

bibliography

|

footnote

|

jacket

|

|

blurb

|

foreword

|

preface

|

|

chapter

|

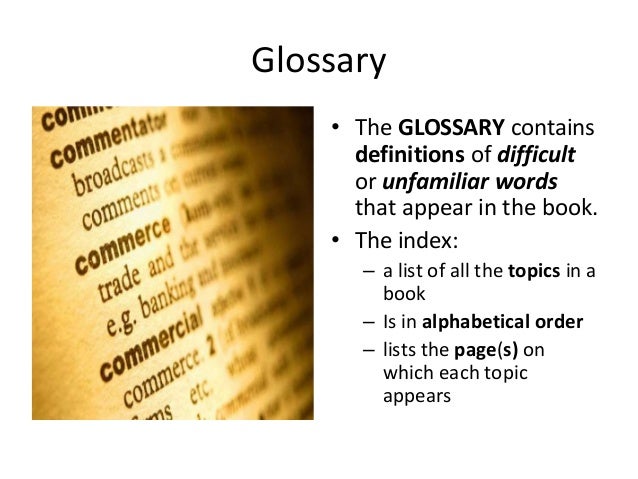

glossary

|

title

|

4 A _________________________ is a list of the books and articles that were used in the preparation of a book. It usually appears at the end.

5 The ________________________ are the photographs or drawings that are found in a book.

6 The __________________________ at the beginning or end of a book are where the author thanks everyone who has helped him or her, plus who supplied photographs, etc.

7 A ___________________________ is an introduction at the beginning of a book, which explains what the book is about or why it was written.

8 A ___________________________ is one of the parts that a book is divided into. It is sometimes given a number or a title.

9 An __________________________ to a book is extra information that is placed after the end of the main text.

10 A ___________________________ is a preface in which someone who knows the writer and his or her work says something about them.

11 An___________________________ is an alphabetical list that is sometimes printed at the back of a book which has the names, subjects, etc. Mentioned in the book and the pages where they can be found.

12 The __________________________ is a list at the beginning of a book saying what it contains.

13 The __________________________ is an alphabetical list of the special or technical words used in a book, with explanations of their meanings.

14 A ____________________________is a note at the bottom of a page in a book which gives the reader more information about something that is mentioned on the page.

15 The __________________________ is a short description by the publisher of the contents of a book, printed on its paper cover or in advertisements.

watch the following videos:

Parts of a book:

1.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DM1_ON0wIE8

2.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQyntYcGwik

Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468)

Pls, learn the basics about Johannes Gutenberg plus learn the vocabulary you can find below the text. In case you wish to download the stuff, just click on the following link J._Gutenberg2017._upravene.docx

Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468)

Johannes Guttenber invented the printing press - the most important invention in modern times.

Without books and computers we wouldn't be able to learn, to pass on information, or to share scientific discoveries. Prior to (before) Gutenberg invented the printing press, making a book was a hard process. It wasn't that hard to write a letter to one person by hand, but to create thousands of books for many people to read was nearly impossible. Without the printing press we wouldn't have had the Scientific Revolution or the Rennaisance. Our world would be very different.

He was born in Mainz, Germany around the year 1398. He was the son of a goldsmith. We do not know much about his childhood. He moved a few times around Germany, but that's all we know for sure.

Inventions

Gutenberg took some existing technologies and some of his own inventions to invent the printing press in the year 1450. One key idea he came up with was moveable type. Rather than use wooden blocks to press ink onto paper, Gutenberg used moveable metal pieces to quickly create pages. He made innovations all the way through the printing process enabling pages to be printed faster. His presses could print thousands of pages per day vs. 40-50 with the old method. This was a dramatic improvement and allowed books to be acquired by the middle class and spread knowledge and education like never before. The invention of the printing press spread rapidly throughout Europe and soon thousands of books were being printed using printing presses.

Among his many contributions to printing are:

- The invention of a process for mass-producing movable type;

- The use of oil-based ink for printing books (farba na olejovom základe)

- Adjustable moulds (nastaviteľné formy)

- Mechanical movable type (mechanická pohyblivá sadzba)

- The use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses (skrutkový lis) of the period

Combination of these elements into a practical system allowed the mass production of printed books.

Gutenberg's method for making type is traditionally considered to have included a type metal alloy (sadzba zhotovená zo zliatiny kovov) and a hand mould (ručná forma) for casting type (odlievanie sadzby). The alloy (zliatina) was a mixture of lead (olova), tin (cínu), and antimony (antimónu) that melted (tavila sa) at a relatively low temperature for faster and more economical casting (odlievanie), cast well (dobre sa odlieval), and created a durable type (a vytvoril trvácnu sadzbu)

First printed books

It is thought that the first printed item using the press was a German poem. Other prints included Latin Grammars and indulgences for the Catholic Church. His real fame came from producing the Gutenberg Bible. It was the first time a Bible was mass-produced and available for anyone outside the church. Bibles were rare and could take up to a year for a priest to transcribe. Gutenberg printed around 200 of these in a relatively short time.

The original Bible was sold for 30 florins. This was a lot of money back then for a commoner, but much, much cheaper than a hand-written version.

There are about 21 complete copies of Gutenberg Bible existing today. One copy is worth about 30 million dollars.

Vocabulary:

Printing press – tlačiarenský stroj invention – vynález

Pass on information – postúpiť, poslať ďalej informáciu

Share scientific discoveries – zdieľať, podeliť sa o vedecké objavy

Prior to – pred, skôr ako invent – vynájsť

Nearly – takmer Scientific Revolution – vedecko-technická revolúcia

Goldsmith – zlatník move – sťahovať sa

For sure – naisto, s istotou key idea –kľúčová/hlavná myšlienka (nápad)

come up with – prísť s čím, vymyslieť moveable type – pohyblivá sadzba

rather than – radšej ako, skôr ako wooden blocks – drevené bloky/kvádre

ink – farba, atrament metal pieces – kovové kusy

all the way through – úplne, v celom enable – umožniť

improvement – zlepšenie allow – dovoliť, povoliť

acquire – získať, dosiahnuť spread – šíriť

knowledge – vedomosti, znalosti education – vzdelanie

mass-produce – masovo vyrábať oil-based ink – farba/atrament na olejovom základe

adjustable – nastaviteľný mould – forma

wooden – drevený similar to – podobný ako

agricultural – poľnohospodársky screw press – skrutkový lis

mass production – masová výroba considered – považovaný

consider – považovať include – zahŕňať

type metal alloy – sadzba zhotovené zo zliatiny kovov alloy – zliatina

hand mould – ručná forma casting type – odlievanie sadzby

type – sadzba mixture – zmes

lead – olovo tin – cín

antimony – antimón melt – taviť sa

low temperature – nízka teplota durable – odolný, trvácny

item – položka, kus German – nemecký

poem – báseň indulgences – odpustky

Catholic Church – katolícka cirkev real – skutočný

Fame – sláva available – dostupný

Rare – vzácny, zriedkavý take up to a year – trvať až rok

Priest – kňaz transcribe – prepísať

Original – pôvodný commoner – bežný človek

Copy – výtlačok worth - hode

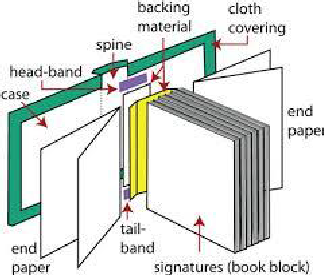

- páska na knihe - belly band

- záložka prebalu - flap (front flap/back flap)

- prebal - dust jacket (includes title, author, illustrator and the publisher on the front and ISBN on the back

- knižný chrbát - spine (book back)

- kapitálik - head band (horný kapitálik) tail band (spodný kapitálik)

- oriezka - edging; horná oriezka - top edge, spodná oriezka - tail edge, fore edge -predná oriezka/okraj

- záložková stužka - flag book mark

- papierová záložka - paper book mark

- chrbátnik - head cap

- polep - gluing

- knižné dosky - boards, back board - zadná doska, front board - predná doska

- knižná drážka vonkajšia - joint

- vnútorná knižná drážka - hinge

- predsádka - endpaper, zadná p. - rear endpaper

- vakát - fly leaf

- knižný hárok - sheet

- list - leaf

- knižná zložka - signature

- kníhviazačstvo - bookbinding

- knižný blok - text blok

- titulný list - title page

- vydavateľský záznam - copyright page

- protititulný obrázok - frontispice

- patitul - half-title/bastard title

- ľavá strana - verso, pravá strana - recto

watch the following videos:

Parts of a book:

1.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DM1_ON0wIE8

2.https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DQyntYcGwik

PARTS OF A BOOK

What is a book's FRONT MATTER?

Front matter is the information that appears up front and first in a book. The front matter contains the nuts and bolts of the book’s publication—information like title, author, publisher, ISBN and Library Congress data. The front matter pages generally aren’t visibly numbered; when they are, the numbers appear as Roman numerals.

Here are the typical parts of a book's front matter:

Half title, sometimes called bastard title — is just the title of the book (you can think of it as a kind of half the title page)

Frontispice — is the piece of artwork on the left (“verso”) side of the page opposite the title page on the right (“recto”) side.

Title page – this is a page which contains the title of the book, the author (or authors) and the publisher.

Copyright page — includes:

the declaration of copyright (that is, who owns the copyright, generally the authors)

- other types of credits, such as illustrators, editorial staff, indexer, etc., and sometimes notes from the publishers

- copyright acknowledgments — for books that contain reprinted material that requires permissions, such as excerpts, song lyrics, etc.

- edition number — this number represents the number of the edition and of the printing. Some books will specifically note “First Edition”; others don’t declare that they are first editions, and instead is represent their printings with a number. In those cases, a first edition would look like:

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

- A second edition would be noted as:

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

- Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data – which includes information such as title, authors, ISBN, Library of Congress number, subject matter, year of publication.

Dedication — where the author honors an individual or individuals by declaring that the labor of the book is “To” [name or names]

Acknowledgements — the author’s thanks to those who contributed time and resources towards the effort of writing the book.

Table of Contents — outlines what is in each chapter of the book.

Foreword — is a “set up” for the book, typically written by someone other than the author.

Preface or Introduction — is a “set up” for the book’s contents, generally by the author.

ISBN

ISBN – International Standard Book Number precisely identifies a book, there should be no two books with the same number. The following publishing of the same book has a new number ISBN.

The International Standard Book Number (ISBN) is a unique numeric commercial book identifier based upon the 9-digit Standard Book Numbering (SBN) code created by Gordon Foster, Emeritus Professor of Statistics at Trinity College, Dublin, for the booksellers and stationers.

The 10-digit ISBN format was developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and was published in 1970 as international standard ISO 2108.

Since 1 January 2007, ISBNs have contained 13 digits, a format that is compatible with "Bookland" European Article Number EAN-13s.

An ISBN is assigned to each edition and variation (except reprintings) of a book. For example, an ebook, a paperback, and a hardcover edition of the same book would each have a different ISBN. The ISBN is 13 digits long if assigned on or after 1 January 2007, and 10 digits long if assigned before 2007.

What is a book's BODY MATTER?

Body matter is the core contents of the book— often divided into segments:

The body matter is numbered with Arabic numerals beginning with the number “1” on the first page of the first chapter.

- Art program — anything that isn’t text (photographs, illustrations, tables, graphs, etc.) is considered to be part of the book’s art program. The art program might be integrated into each page or appear all together within a separate “signature” somewhere in the book.

In non-fiction literature there there could be:

- marginálie – marginalia

- poznámky pod čiarou – footnotes

- záhlavie- header, heading

What is a book's END MATTER?

End matter is the materials at the back of the book, generally optional.

Glossary — this is a listing and definitions of terms that might be unfamiliar to the reader.

Bibliography – most often seen in non-fiction like biography or in academic books,

a bibliography lists the reference sources used in researching the book.

Index – the index is placed at the end of the book, and lists all the major references in the book (such as major topics, mentions of key people in the book, etc.) and their specific, corresponding page numbers.

Publishing imprint: publishing and printing data: author(s), title, publisher, edition, printing house where a book was printed, circulation, number of publisher’s sheets, number of author’s sheets, production number

Errata (sg. erratum) – publishers issue an erratum for a production error

13 March

PLS, FINISH THIS TASK.

You have decided to contribute to your school magazine and write an article about your school trip. You have just come back from an English-speaking country.

Within your article include

-

where you went and how

-

accommodation and food

-

places of interest you visited and what you liked about them

-

what you did there and what happened (positive and negative event)

-

the best bit (what you liked most)

-

(B1 160-180 words, B2 200-220 word

WRITING AN ARTICLE

AN ARTICLE is usually written for an English-language magazine or newsletter. The main purpose is to inform, interest and engage the reader, so there should be some opinion or comment.

Hints

-

Add a short title to catch the reader's attention. Make sure it is relevant. You can use the one in the question or invent one of your own.

-

Introduce the topic. Although you don't know the readers personally, you can address them directly and ask them a rhetorical question. It helps to involve them.

-

Divide your report into sections according to the input. One or two paragraphs will do.

-

Develop the ideas in the task input. Remember .

-

Use a personal or more neutral style, but not formal (you might use contractions).

-

It is important that you show a range of structures.

-

Give examples where appropriate to bring your article to life

-

Use humour where appropriate.

-

Give a conclusion and summary in the last paragraph.

-

-

Useful language for an article

Involving the reader

If the answer is ..., you should.... What would live be like if..

Making the article lively and interesting

-

I was absolutely terrified when I realised... More importantly, it was something I...Not surprisingly, it's a good way of raising money. The tent was worryingly small for three people! It was the most amazing experience I have ever had

Developing your points

Giving your own opinion

Article – Model question 1

A charity event to remember

What is the most unusual way you've raised money for charity? How did you do it? What did you have to do? Was the event a success? Would you do it again?

Write us an article answering these questions.

We will publish the best articles on our website.

Write your article in 140-190 words in an appropriate style.

Article - Model answer 1

A charity event to remember

So why did I decide to do a 90-km walk in six days along the Great Wall of China? Well, the reason was that our local children's hospital needed to raise money or it would be close. However, I didn't realise how big a challenge it would be.

Before I went, I thought that I would be walking along a flat surface but when I saw the Great Wall, my heart sank. Part of the time we would be trekking up hundreds of high steps and, worryingly, some of the paths had steep falls on either side and there was nowhere to go because we were surrounded by mountains and forests. However, after a while, I started to love the experience. I was in one of the most amazing places on earth and the views were incredible.

In the end, the adventure was a great success. The hospital was delighted because a group of us managed to raise several thousand pounds.

Would I be keen to help the hospital again next year? Yes, but I think I'll try and find an easier challenge next time!

[+/- 190 words]

Article - Model question 2

TASK: You see this announcement in an international magazine.

Life on a desert island

Imagine you were on a desert island. What important object, person or place in your life would you miss most? What would be the reasons?

Write us an article answering these questions.

We will publish the best articles in the magazine.

Write your article in 140-190 words in an appropriate style.

Article - Model answer 2

Life on a desert island

How would you feel about living on a desert island? I can't imagine anything worse! I'd miss a lot of things but most of all, I would miss my home.

My home is a small house on the outskirts of a city. It was built about 50 years ago and has a small garden. In the summer, our country gets very hot but our house is always cool. You'd probably think our house is nothing special, but I have lived there all my life and all my friends live nearby. It's a happy place, where I feel completely safe. Whenever I go away, I look forward to coming back, lying on my bed, reading a book and listening to my brother and sister arguing downstairs!

I love travelling and meeting new people, but if I were on a desert island, I'd be away from the place I love most: my home; and I would hate that. [+/- 160 words]

Article- Model question 3

TASK

You see this announcement in an international magazine.

Articles wanted

Lucky winners

What would you do if you won a large sume of money. How would your life change?

Write us an article answering these questions. Give reasons.

We will publish the best articles next month.

Write your article in 140-190 words in an appropriate style.

Article - Model answer 3

Don't throw it all away!

Have you ever dreamt of becoming rich unexpectedly? Just imagine what your life would be like! However, some people who get rich quickly are very careless with their money and end up being poorer than they were before.

That's why I'd be very careful. I wouldn't want a completely different kind of life, so I'd start by putting some of it away, in case everything went wrong - set up a kind of "emergency fund". Then I would buy my hard-working parents a new home. They deserve it because they have always provided me with everything I've always wanted, even if it meant they had to go without. I would also give some money away to needy people who are struggling in the world and have no food. It would not be right to just spend the money on myself. Then I think I would take a year off from studying and travel round the world in great comfort. I've spent most of my live travelling on a limited budget and sleeping in hostels.

After that, who knows? I'll see, but I certainly won't be buying any luxury cars

Revise how to write an essay and focus on 4 model answers.

ESSAY WRITING

The essay should be well organised, with an introduction and an appropriate conclusion and should be written in an appropriate language and tone.

It is easier to have a balanced discussion comparing advantages and disadvantages, or ideas for and against a topic.

-

Read essay question and prompts very carefully in order to understand what you are expected to do.

-

All your ideas and opinions are relevant to the question.

-

Support your opinions with reasons and examples.

-

Think of a third idea of your own in addition to the two given prompts.

-

Ideas need to be expressed in a clear an logical way, and should be well organised and coherent. It is advisable to use up to 5 paragraphs:

-

Introduction

-

Prompt 1 development + reason(s)/example(s)

-

Prompt 2 development + reason(s)/example(s)

-

Prompt 3 development + reason(s)/example(s)

-

Conclusion (you may include your opinion here)

-

Varying the length of the sentences, using direct and indirect questions and using a variety of structures and vocabulary may all help to communicate ideas more effectively.

-

The correct use of linking words and phrases (e.g. but, so, however, on the other hand, etc.) and cohesive devices (e.g. using pronouns for referencing) is especially important in essays.

Hints

-

[INTRODUCTION and CONCLUSION]

- In the introduction, state the topic clearly, give a brief outline of the issue, saying why it is important or why people have different opinions about it.

- DO NOT express your opinion at the beginning of your essay.

- DO give your opinion in the final paragraph.

-

[SECOND and THIRD PARAGRAPHS]

- Each new paragraph has one main idea, stated in a topic sentence.

- Include relevant details to support the main idea: these might include examples, rhetorical questions (do no overdo it), controversial or surprising statements... If you include a drawback, give a possible solution, too.

-

[GENERAL]

- DO use a relatively formal language and an objective tone. Do not be too emotional.

- Remember to use linking adverbials to organise your ideas and to make it easy for the reader to follow your argument.

- In the exam, allow yourself time to check your grammar, spelling and punctuation thoroughly.

Linking words and phrases

Present your ideas clearly. Use connectors to link your ideas

Make sure you know how to use connectors appropriately (register, punctuation...). If you have any doubts, you should use a good dictionary to check.

-

To express personal opinions: In my opinion, I believe (that) / I feel (that) / it seems to me / in my view /as I see it / I think / personally

-

To show purpose: to / in order to / so as to / so that

-

To list ideas: Firstly / secondly / finally / In the first place / Lastly

-

To contrast ideas: However / although / in contrast / whereas / but / nevertheless / in spite of / despite

-

To describe a cause: Because / since / as / due to

-

To show a sequence: First of all / then / after that / eventually / in the end / finally

-

To add information: In addition / moreover / what is more / besides / too / furthermore / and

-

To describe a consequence: Consequently / as a result / therefore / so / thus / for this reason / that is why

-

To conclude the topic: In conclusion / to sum up / in short / all in all

Model questions and answers

Essay 1

TASK

Is is a good thing that countries spend a lot of money on their heritage?

Notes

Write about:

1. preserving the past

2. investing in the future

3. ________ (your own idea)

Write your essay in 140-190 words in an appropriate style.

Essay 1 - Model answer

Most countries spend large sums of money protecting their national heritage. However, there is strong argument that we should look forwards and not backwards, spending less money on preserving the past and more on securing our future.

On the one hand, it is important that we remember our heritage. Once it is lost, it is lost forever. Caring for important monuments helps with this. It also attracts tourists, which has an economic benefit for everyone.

On the other hand, governments spend a lot of money on museums and keeping historic sites in good condition when poor people need houses to live in and businesses need better roads for transporting their goods.

Another argument is that by making heritage sites attractive for tourists -for example, by putting on entertainment - we give a very untrue picture of the past and sometimes damage the local environment.

To conclude, while there are strong arguments for not spending too much on preserving the past, I believe it is important to protect the most famous sites for the future generations but it is not realistic to try and save everything. We need to invest in the future too.

(+/- 190 words)

Essay 2 - Model question

TASK

Science is very important in the 21st century. How do you think it could be made more appealing to young people?

Notes

Write about:

1. television programmes

2. interactive museums

3. ________ (your own idea)

Write your essay in 140-190 words in an appropriate style.

Essay 2 - Model answer

Although young people love gadgets and technology, some see science as uninteresting and 'uncool'. Over time, the number of young people, particularly girls, pursuing science and technology studies and careers has dropped.

One way in which science could be made more attractive would be to have lively television programmes presented by celebrities, with subjects which were relevant to the experience of the young. We live in a celebrity culture and children identify with well-known young people.

Another idea would be to set up interactive science museums in every town, where parents could take their children. It is much better to teach children the principles of science through hands-on experiments than to lecture them in a classroom.

Of course, there would be more incentives if the average scientit were better paid and young people were made aware of the range of jobs available. A lot of people are put off a scientific career because they think it means working in a badly paid job in a boring laboratory.

Whichever way we choose, it is vital that more young people are attracted to science, since society's prosperity depends largely on continuous scientific progress.

(+/- 190 words)

Essay 3 - Model question

TASK

Is it better to live alone or with someone else?

Notes

Write about:

1. independence

2. money

3. ________ (your own idea)

Write your essay in 140-190 words in an appropriate style.

Essay 3 - Model answer

Nowadays more people are deciding to live by themselves. Some people claim this is more enjoyable and in young people it develops a sense of responsibility, whereas others disagree.

The main advantage of living alone is that there is nobody to tell you what to do, so you can live your life in your own way. What is more, you can organise or decorate your house as you want. There is no one else to disagree with.

On the other hand, it can be quite lonely for some people. By nature, we are social animals. Secondly, it is more expensive because you have to pay all the rent and bills yourself, so you have less money to enjoy yourself. Last but not least, it can be quite hard to find a nice flat for one person, so you might not be able to live in the best area.

To sum up, there are strong arguments on both sides. In conclusion, I believe that living alone is better for older people who have more money and like privacy but not for young people who need to share the costs.

(+/- 180 words)

Essay 4 - Model question

TASK

Whether you are happy or not depends on the personality you are born with. Do you agree?

Notes

Write about:

1. money

2. health

3. ________ (your own idea)

Write your essay in 140-190 words in an appropriate style.

Essay 4 - Model answer

Some people claim they are naturally cheerful. However, in my view, how we lead our lives is the main reason we are either happy or unhappy.

Take money, for example. Money doesn't automatically make us happy. In fact, it makes some people very unhappy because they are frightened of losing what they've got. On the other hand, if we're not greedy and don't spend it foolishly, it can reduce stress and give us security.

Then consider health. If we eat badly, get too little sleep and don't exercise, our health will decline and make us miserable. Eating well and going for lovely long walks in the countryside can make us feel better generally.

The third thing I think is important is to have a positive outlook on life. We should all enluy things like music and being with our friends. At the same time, it's important to spend time alone and live as simply as possible, which is not easy in the 21st century!

All these make a big difference to our happiness, no matter what our natural temperament.

(+/- 170 words)

10th March

REVISION: IRREGULAR VERBS

http://www.gjar-po.sk/~visnovskyt4d/irregularverbs.pdf

Learn FASHION (the worksheet and vocabulary list). Think over the tasks and answer the questions.

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_1.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_2.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_3.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_7.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_8.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_9.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_10.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_11.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_20.htm

DEPENDENT PREPOSITIONS

https://elt.oup.com/student/englishfile/intermediate3/vocabulary/dependent_prepositions/?cc=hr&selLanguage=en

http://www.perfect-english-grammar.com/verbs-and-prepositions-exercise-1.html

http://speakspeak.com/english-grammar-exercises/intermediate/verb-and-preposition-combinations

GRAMMAR BANK page 147/ 8B ex.a ,b

Prosím, v piatok tento týždeň odovzdáte nasledovné slohy. Upozorňujem vás, že v piatok je záväzný termín, nakoľko je nutné, aby som s vami tie slohy prešla a povedali sme si, čo tam musí byť a ako to napísať. Ak neviete, ako sa píše článok, resp. list, máte vzory na tabe s názvom writing.

témy:

1. Článok do časopisu (úprava: úvod - všeobecný, jadro - môj hrdina, pričom môžete každý bod rozvinúť v samostatnom odstavci, záver - zhrnutie a posledný bod zadania, čo je vlastne váš názor)

Role Models and Idols

You decided to contribute to the magazine PEOPLE AROUND US and write an article (160-180 words) about a person who is your hero. Answer the following questions:

- Is it a real person or a film/literature hero?

- What does your hero look like? Describe his/her appearance.

- What are some of the traits (črty) that make this person a hero to you?

- What is his/her lifestyle like? Describe his/her habits

- Do you want to live like your hero? Why yes/why not?

2. List priateľovi/rozprávanie príbehu (pozor na úpravu: adresa, dátum, oslovenie, štruktúra, odstavce, zdvorilostná formulka..)

téma: The worst/best holiday/day in my life

Write a letter (160-180 words) to your English penfriend about the worst/best day/holiday of your life. Include the following points:

- where you went and how

- who you went with

- what you did there

- what happened

Pozor - použite minulé časy - jednoduchý, priebehový aj predminulý (jednoduchý, priebehový)

Prehľad časov nájdete pod TAB GRAMMAR

http://www.englishguide.sk/test-english-tenses-review-1/

I will tell you more about the test after your spring holiday. You will have been revising by that time: Reported speech, conditionals, relative clauses and question tags + VOCABULARY BANK IN EF the topic EDUCATION

For those students who were absent at school on 17th February (Friday):

The latest grammar was explained and practised: Grammar bank 150-151 + WB 63, 66/2Grammar ex. a,b. Do the exercises yourselves! Consultation possible.

Grammar bank 146 / revise Reported speech and do the two exercises +

http://www.englisch-hilfen.de/en/exercises_list/reported.htm

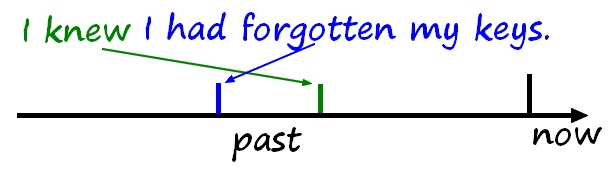

REPORTED/INDIRECT SPEECH

Backshift

You must change the tense if the introductory clause is in Simple Past (e. g. He said). This is called backshift. Example:

He said, “I am happy.” – He said that he was happy.

|

Direct Speech

|

Reported Speech

|

|

Simple Present

|

Simple Past

|

|

Present Progressive

|

Past Progressive

|

|

Simple Past

|

Past Perfect Simple

|

|

Present Perfect Simple

|

|

Past Perfect Simple

|

|

Past Progressive

|

Past Perfect Progressive

|

|

Present Perfect Progressive

|

|

Past Perfect Progressive

|

|

Future I (going to)

|

was / were going to

|

|

Future I (will)

|

Conditional I (would)

|

|

Conditional I (would)

|

The verbs could, should, would, might, must, needn’t, ought to, used to do not normally change.

Example:

He said, “She might be right.” – He said that she might be right.

In the following table, you will find ways of transforming place and time expressions into reported speech.

|

Direct Speech

|

Reported Speech

|

|

today

|

that day

|

|

now

|

then

|

|

yesterday

|

the day before

|

|

… days ago

|

… days before

|

|

last week

|

the week before

|

|

next year

|

the following year

|

|

tomorrow

|

the next day / the following day

|

|

here

|

there

|

|

this

|

that

|

|

these

|

those

|

REPORTED SPEECH/Indirect speech

http://www.englisch-hilfen.de/en/exercises_list/reported.htm

http://www.ego4u.com/en/cram-up/grammar/reported-speech

http://www.usingenglish.com/quizzes/102.html

http://www.ego4u.com/en/cram-up/grammar/reported-speech/exercises?09

http://www.ego4u.com/en/cram-up/grammar/reported-speech/exercises?04

http://www.ego4u.com/en/cram-up/grammar/reported-speech/exercises?06

REVISE CONDITIONALS I, II, III

http://www.perfect-english-grammar.com/conditionals.html

http://www.perfect-english-grammar.com/first-second-third-conditionals-exercise.html

Conditional sentences

Conditional sentences are sometimes confusing for learners of English as a second language.

Watch out:

- Which type of conditional sentences is it?

- Where is the if-clause (e.g. at the beginning or at the end of the conditional sentence)?

There are three types of conditional sentences.

1. Form

2. Examples (if-clause at the beginning)

3. Examples (if-clause at the end)

4. Examples (affirmative and negative sentences)

* We can substitute could or might for would (should, may or must are sometimes possible, too).

- I would pass the exam.

- I could pass the exam.

- I might pass the exam.

- I may pass the exam.

- I should pass the exam.

- I must pass the exam.

Verb Patterns - see the explanation below

môžete si precvičiť http://www.helpforenglish.cz/article/2008083006-test-verb-patterns-1

http://www.helpforenglish.cz/article/2008110205-test-verb-patterns-2

http://www.helpforenglish.cz/article/2011102302-test-verb-patterns-3

gerundium vs infinitív http://www.helpforenglish.cz/article/2006071601-gerundium-vs-infinitiv-cviceni-1

http://www.helpforenglish.cz/article/2006071602-gerundium-vs-infinitiv-cviceni-2

http://www.helpforenglish.cz/article/2006071702-gerundium-vs-infinitiv-cviceni-3

Verb Patterns (slovesné vzorce)

Slovesné vzorce, ač to zní matematicky, nemají s matematikou nic společného a jedná se v podstatě o jev, kdy se nám ve větě objeví dvě slovesa za sebou.

Budu konkrétní:

I can ski. – sloveso v infinitivu bez TO

I want to ski. – sloveso v infinitivu s TO

I enjoy skiing. – sloveso v gerundiu (-ing)

I talked about skiing. – slovesná vazba s předložkou

Sečteno a podtrženo, s jinými tvary druhého slovesa ve větě se nemůžete v angličtině setkat. Problém je však v tom, kdy který tvar zvolit a pravidla tady bohužel jsou jen minimální. Proto nezbývá nic jiného, než se naučit každé sloveso a jeho “vzorec” samostatně.

Není třeba nikam spěchat. Mírně pokročilí studenti (a někdy i začátečníci) asi už znají všechny čtyři výše zmíněné příklady. Úmyslně jsem v úvodu zvolil slovesa základní, která patří do základní slovní zásoby.

S vyšší pokročilostí ovšem přibývají další a další slovesa, ale jelikož se s nimi nesetkáte tak často jako např. se slovesem WANT, nemusíte si být jisti, který tvar druhého zvolit. Pokročilejší studenti se pak vzorce musí jednoduše naučit / nadrtit / nabiflovat.

Slovesa následovaná infinitivem bez TO

V této kategorii je sloves naštěstí jen několik. Hlavně jde o modální slovesa, kde studenti většinou nechybují.

1) modální (způsobová) slovesa

základní = can, may, must

pokročilejší = could, might, will, would, shall, should

I can do it.

May I help you?

You must obey!

Podrobný článek o modálních slovesech si můžete přečíst zde

2) slovesa LET a MAKE

Další dvě specifická slovesa jsou LET a MAKE.

Let me open the door for you.

Don't make me laugh!

V trpném rodě se sloveso MAKE váže s inifitivem s TO:

I was made to do it.

3) sloveso HELP

Se slovesem HELP můžete použít infinitiv bez TO, ale také s TO:

He helped her open the door.

He helped her to open the door.

4) sloveso DARE

Poslední v této kategorii je sloveso DARE (opovážit se, troufnout si), které může být modální (způsobové) sloveso, a váže se tady s infinitivem bez TO. Pracujeme s ním pak jako s modálním slovesem.

zápor: DARE + NOT = DAREN'T

otázka: DARE YOU…?

Používá se však i jako běžné sloveso, se kterým pracujete jednoduše a váže se s infinitivem s TO, ale také bez TO.

zápor: DON'T DARE

otázka: DO YOU DARE…?

Jako modální sloveso (bez TO):

I dare not go. = I daren't go.

Dare you do it?

How dare you do it?

Jako běžné sloveso (s TO i bez TO):

I didn't dare (to) go.

Do you dare (to) do it?

Nobody dared (to) speak.

Slovíčko DARE patří také do kategorie sloves, po kterých je nejprve předmět a poté infinitiv (tato kategorie je zmíněna níže), a znamená pak “vyzvat někoho k něčemu”

I dare you to drink it!

Samostatný článek o slovesu DARE si můžete přečíst zde

Slovesa následovaná infinitivem s TO

Tato kategorie je společně s následující kategorií ‘gerundium’ nejobsáhlejší, a taky se pokročilejším studentům nejčastěji plete.

“Bude po slovese infinitiv nebo gerundium?” Nezbývá nic jiného, než se naučit jednotlivá slovesa.

Bohužel není vše černobílé a anglická gramatika je toho důkazem. Problematika INFINITIV vs. GERUNDIUM není jen o tom naučit se zpaměti všechna spojení. Jde to ještě dál: některá slovesa se mohou pojit s infinitivem NEBO s gerundiem a nedochází ke změně významu. Jsou tu však i taková slovesa, kde dochází ke změně ve významu. Více se dozvíte níže.

Ale nepředbíhejme. Následují příklady sloves, po kterých je infinitiv. (obsáhlejší seznam naleznete níže)

Slovesa v této kategorii se dají rozdělit na dvě základní skupiny:

1) slovesa, po kterých je přímo infinitiv

afford: I couldn't afford to buy the book.

agree: Susan agreed to help them.

appear: He appears to be tired.

decide: I have decided to leave on Friday.

hesitate: Don't hesitate to contact us.

hope: Jack hopes to arrive on Saturday.

offer : They offered to help us.

plan : I am planning to have a party.

refuse: I simply refuse to believe it.

want: I want to tell you the truth.

wish: She wishes to come with us.

2) slovesa, po kterých je nejprve předmět a pak infinitiv

ask: I asked Jim to help us.

expect: I expect you to be here on Monday.

hire: She hired a boy to mow the lawn.

instruct: He instructed them to be careful.

invite: Harry invited the Jacksons to come to his party.

lead: The article leads me to believe it's true.

order: The judge ordered me to pay a fine. teach: My brother taught me to swim.

want: I want you to do it.

Určitě si všimnete, že některá slovesa jsou v obou kategoriích – může po nich být přímo infinitiv, nebo nejprve zájmeno a až pak infinitiv. Např:

I want to do it.

I want you to do it.

Slovesa a vazby následované gerundiem (-ing)

Další velice obsáhlá sekce jsou slovíčka následovaná gerundiem (sloveso zakončeno -ing). I tato kategorie má několik podsekcí, jelikož sem patří i určité vazby. Opět si uvedeme jen několik příkladů, podrobnější seznam najdete níže.

1) slovesa následovaná gerundiem (-ing)

admit: He admitted stealing the money.

avoid: He avoided answering my question.

deny: She denied committing the crime.

enjoy: We enjoyed visiting them.

fancy: I don't really fancy doing it.

imagine: Can you imagine living here?

keep: I keep hoping he will come.miss: I miss being with my family.

postpone: Let's postpone leaving until tomorrow.

quit: He quit trying to solve the issue.

recall: I don't recall meeting him before.

recommend: I recommended calling her.

suggest: She suggested going to the cinema.

Pozor si dejte například na sloveso suggest:

She suggested going to the cinema.

She suggested that he go to the cinema.

Podobně se chovají například slovesa recommend, propose, request, insist atd. Tento pro mnohé zvlášní gramatický jev se jmenuje konjunktiv a více se o něm dočtete v samostatném článku zde.

2) vazby se slovesem GO

Pokud jdeme nebo jedeme dělat nějakou činnost (většinou sport nebo hobby), používáme sloveso GO, po kterém je také vždy gerundium. Zde jsou příklady:

go bowling, go camping, go canoeing, go dancing, go fishing, go hiking, gohunting, go jogging, go running, go sailing, go shopping, go sightseeing, goskating, go skateboarding, go skiing, go swimming

I usually go swimming in summer.

I went shopping yesterday.

Po slovesu GO může být i infinitiv (s TO i bez TO), pokud se nejedná například o oblíbenou činnost, ale o konstatování, že jdete něco udělat:

I should go to see a doctor.

I should go see a doctor.

I should go and see a doctor.

POZOR!

Zde bych rád zmínil jednu typickou chybu.

Pokud chci říct Uvažuji, že pojedu lyžovat, dochází k zajímavému jevu:

jet lyžovat = go skiing (vazba se slovesem go, viz výše)

uvažovat = consider (sloveso, po kterém je vždy gerundium)

Celá tato věta je v přítomné čase průběhovém, proto:

I am considering going skiing.

Ano, budou tady tři slovesa s koncovkou -ING za sebou.

Jedná se o průběhový čas, proto I AM CONSIDERING.

Sloveso ‘consider’ se váže vždy s gerundiem, proto je GOING.

‘Jet lyžovat’ je ve vazbě GO SKIING.

Studenti se na konci věty většinou “vylekají” a řeknou si, že nemůže být ING 3× za sebou a udělají chybu jako třeba I am considering going to ski.

Tady jsou jasná pravidla a není důvod je porušovat, i když se vám zdá, že “to tak přece nemůže být”.

3) ustálená spojení následovaná gerundiem

Zde bych rád nakousl ještě jednu kategorii. Nejedná se o klasický slovesný vzorec, protože se tady nebudou za sebe klást dvě slovesa, ale jedná se přímo o vazby.

have a good time: We had a good time playing soccer.

have a hard time: We had a hard time finding the house.

have a difficult time: I will have a difficult time making up my mind.

have fun: We had fun playing football.

have trouble: We had trouble looking for our car.

have difficulty: We had difficulty filling in the form.

4) vazby sloves s předložkami (následované gerundiem)

Asi nebude novinkou, že po předložkách je vždy gerundium, ale problém je vybrat tu správnou předložku. Tady opět nezbývá nic jiného, než se tyto vazby naučit. Proto bez dlouhého vysvětlování následuje seznam těch nejužitečnějších:

ABOUT

argue about: We argued about going on holidays.

be excited about: I am excited about going on holiday.

be thrilled about: I was thrilled about going camping.

be worried about: I am worried about taking the exam.

ABOUT / OF

complain about / of: Susan complained about having a headache.

dream about / of: I dream about going to Hawaii.

speak about / of: He spoke about being concerned about his health.

talk about / of: Peter talked about being too busy.

think about / of: I was thinking about going on holiday.

FOR

apologize for: David apologized for being late.

be responsible for: Who is responsible for taking care of invoices?

be thankful for: I was thankful for not having to go there.

blame (sb) for: Don't blame me for breaking it.

forgive (sb) for: Please forgive me for doing that.

have an excuse for: He always has an excuse for not coming.

have a reason for: Paul has a good reason for doing it.

thank (sb) for: Thank you for coming.

FROM

discourage (sb) from: My girlfriend discourages me from racing.

keep (sb) from: She kept me from finishing the task.

prevent (sb) from: He prevented her from going there.

prohibit (sb) from: Paul prohibited us from smoking.

stop (sb) from: He stopped the child from running into the street.

IN

believe in: I believe in doing good deeds.

be interested in: I am interested in skiing.

participate in: He participated in searching.

succeed in: She succeeded in setting up her own business.

OF

approve of: My parents don't approve of me coming home so late.

be accused of: She was accused of stealing the present.

be capable of: He isn't capable of telling lies.

be guilty of: The jury found him guilty of stealing the bike.

be tired of: I am tired of having to work all day.

instead of: *Instead of* watching TV, I decided to go to the cinema.

take advantage of: You should take advantage of living here.

take care of: She took care of welcoming the guest.

ON

concentrate on: I concentrated on doing it perfectly.

depend on: Our health depends on taking time to recharge our batteries.

insist on: I insist on knowing the whole truth!

plan on : I'm planning on attending the meeting.

rely on: I really relied on being accepted to that school.

TO

admit to: She admitted to going there secretly.

be accustomed to : I am accustomed to working late hours.

be committed to : We are committed to providing the best medical care.

be opposed to: She was opposed to him doing such things.

be used to: I am used to getting up early.

confess to: She confessed to having an affair.

look forward to: I look forward to seeing you.

object to: I object to him saying such things.

POZOR!

Poslední část je pro studenty nejsložitější. Má to jeden velmi prostý důvod – předložka TO. Problém je v tom, že tady je TO předložka, a proto je po ní gerundium (to going). Jenže slovíčko TO může být taky částice infinitivu (to go).

A v tom je právě kámen úrazu. Studenti mají tak silně zakořeněnou právě infinitivní vazbu TO GO, že jim spojení TO GOING přijde jednoduše špatně.

Výsledkem je pak klasická chyba např. v dopisech: I look forward to see you.

Sloveso těšit se (look forward) je vždy následováno předložkou TO.

těšit se NA něco = look forward TO something

I look forward to seeing you.

Několikrát se mi stalo, že mi studenti jednoduše nevěřili, protože již tolikrát viděli v dopisech např. “I look forward to see you” nebo “I look forward to hear from you.”

Pokud se vám to taky nezdá, tak přemýšlejte se mnou:

go swimming = jít plavat

I talked about going swimming.

Tady vás spojení about going asi nepřekvapí. ABOUT je přece předložka.

I am looking forward to going swimming.

Tady je spojení to going a i zde je předložka, tentokrát TO.

Stejné by to bylo napřiklad v další klasické chybě

I am used to get up early.

jsem zvyklý NA něco = I am used TO something

TO je tady předložka, proto bude správně věta:

I am used to getting up early.

INFINITIV vs. GERUNDIUM

Když se na tento gramatický jev podíváte jako na celek, tak zjístíte, že první krátká kategorie sloves, po kterých je infinitiv bez TO, je docela jasná – jde skoro výhradně o modální (způsobová) slovesa. Další kategorie jsou vazby. Co je ovšem největší problém i pro pokročilé studenty, to je INFINITIV vs. GERUNDIUM.

Jak jsme si ukázali výše, někdy je po slovesech infinitiv, někdy gerundium. V odstavcích výše bylo jen několik příkladových sloves, podrobnější seznam najdete v závěru článku.

Další problém však je, že některá slovesa se mohou pojit jak s infinitivem, tak s gerundiem. A někdy dochází ke změně ve významu a někdy ne.

1) infinitiv vs. gerundium – bez změny významu

Jako první uvedu slovesa z té jedodušší kategorie – ať po nich dáte infinitiv nebo gerundium, význam zůstává stejný:

advise: She advised me to wait. / She advised waiting.

can't bear: I can't bear to wait / waiting in long lines.

begin: It began to rain / raining.

continue: He continued to speak / speaking.

prefer: Janet prefers to walk home. / I prefer walking to running.

start: It started to rain / raining.

V zásadě však platí pravidlo, že pokud je již ve větě jedno gerundium, a my si můžeme vybrat, volíme infinitiv: It's starting raining It's starting to rain

Pokud ve větě gerundium není, výběr je na nás:

It started raining = It started to rain

Malý problém nastává u sloves ADVISE a PREFER – jejich význam se však nemění:

ADVISE

Uvedeme-li ve větě předmět, musíme použít infinitiv:

He advised me to buy a Volvo.

Bez předmětu je pak nutno použít gerundium:

He advised buying a Volvo.

V trpném rodě je však i bez zájmena infinitiv:

I was advised to buy a Volvo.

PREFER

Samotné sloveso PREFER se váže většinou s infinitivem:

I prefer to stay home.

Se slovesem PREFER se však váže předložka TO, jako např. ve větě:

I prefer tea to coffee.

Proto musíme použít u dalších sloves gerundium:

I prefer staying home to going to the concert.

S infinitivem je to taky možné, ale věta bude složitější:

I'd prefer to stay home rather than to go to the concert.

Ve zkrácené podobě pak:

I'd prefer to stay home than go to the concert.

2) infinitiv vs. gerunidum – změna ve významu

Některá slovesa se vážou s infinitivem i gerundiem, ale dochází ke změně ve významu:

REMEMBER + FORGET

U těchto dvou sloves platí stejné pravidlo, proto si je vysvětlíme společně.

She always remembers to lock the door.

He often forgets to lock the door.

Ve větách výše chronologicky nejprve přichází děj slovesa remember / forget a pak činnost:

nejprve si vzpomene, pak zamkne

nejprve zapomene, aby pak zamkl

I remember seeing the Alps for the first time.

I'll never forget seeing the Alps.

V těchto větách naopak nejprve přišla nějaká činnost, na kterou budu vzpomínat nebo zapomenu:

nejprve jsme viděl Alpy, a to si pak budu pamatovat

nejprve jsem viděl Alpy, a na to pak nikdy nezapomenu

Pro lepší pochopení se nyní pojďme věty se zamykáním a Alpami přehodit:

She remembered to lock the door. X She remembers locking the door.

She remembered to see the Alps. X She remembers seeing the Alps.

She forgot to lock the door. X She forgot locking the door.

She forgot to see the Alps. X She forgot seeing the Alps.

REGRET

Podobné je to se slovesem regret. Když použiji infinitiv, nejprve lituji toho, co pak udělám. Naopak pokud použiji gerundium, lituji toho, co jsem před tím udělal:

I regret to tell you that you failed the test.

I regret lending him the money.

HATE

Podobně i zde, pokud použijete infinitiv, jste neradi, že musíte něco udělat. Gerundium naopak označuje obecnou nevoli:

I hate to tell you that you failed the test.

I hate making such stupid mistakes.

TRY

Se slovesem TRY je to trochu jinak. Pokud použijeme infinitiv, pokusíme se něco udělat. Nevíme, jestli se nám to podaří.

Pokud použijeme gerundium, pak víme, že se nám to podaří, ale jde nám o výsledek.

I'm trying to learn English.

Can you try to open the window? I think it's stuck.

The room was hot. I tried opening the window, but it didn't help.

LIKE

Rozdíl mezi použitím gerundia a infinitivu je pouze drobný:

I like going to the cinema.

They like working out.

He likes to go swimming in the morning.

She likes to buy a strong coffee before work.

Zde si můžeme pomoci tím, že pokud se bavíme obecně, použijeme gerundium. Naopak pokud se bavíme o konkrétnější situaci, použijeme infinitiv. Dokonce třeba ani nechceme říct, že je to naše oblíbená činnost, ale prostě to rádi děláme z nějakého důvodu.

Toto pravidlo však rozhodně není černobílé. Například v AmE se setkáte nejčastěji s infinitivem.

NEED

Za sloveso NEED dáváme běžně infinitiv:

You need to go there and tell him.

We need Chris to help us.

Pokud však říkáme, že něco potřebuje nějakou činnost, a někdo to musí udělat, použijeme gerundium:

The car needs washing.

MEAN

Sloveso MEAN má dva základní významy. Pokud vyjadřuje “znamenat” a zajímá nás výsledek, použijeme gerundium:

Do you really want to pass the test? It will mean studying very hard.

MEAN ale může znamenat také “zamýšlet, mít v úmyslu”. Pak použijeme infinitiv:

I didn't mean to hurt you.

STOP

Pozor na sloveso STOP. Je po něm pochopitelně gerundium (stejně jako po všech slovesech, která znamenají ukončení činnosti). Ale lze po něm použít také infinitiv účelu:

I stopped smoking. = Přestal jsem kouřit.

I stopped to smoke. = Zastavil jsem se, abych si zakouřil.

infinitiv vs. gerundium – obecná pomůcka

Pokud jste v situaci, kdy se máte rozhodnou jestli po daném slovese bude infinitiv nebo gerundium, a nemáte po ruce žádný seznam nebo jinou pomůcku, můžete se řídit následujícím:

Gerundium se často používá v případě, že činnost popisovaná druhým slovesem se odehrává před činností popisovanou prvním slovesem:

She denied stealing the money. = popírá něco, co udělala dříve

Infinitiv má opačné pravidlo: sloveso první se odehrává před slovesem druhým, časově jdou slovesa chronologicky po sobě:

She decided to steal the money. = nejprve se rozhodla a pak ukradla

Toto pravidlo však není zdaleka stoprocentní.

Slovesa HEAR a SEE

Slovesa smyslového vnímání HEAR a SEE mají svá specifika a nehodí se do žádné výše uvedené kategorie.

Lze po nich použít infinitiv bez TO nebo gerundium a i zde dochází k mírné změně ve významu, která souvisí s českou dokonavostí a nedokonavostí:

I saw him cross the street.

I saw him crossing the street.

He saw the tree fall down.

He saw the tree falling down.

I heard her knock on the door.

I heard her knocking on the door.

She heard her parents argue in their bedroom.

She heard he parents arguing in their bedroom.

Pokud použijete infinitiv (bez TO), vyjadřujete, že jste viděli nebo slyšeli celou akci. Naopak při použití gerundia vyjadřujete, že jste viděli či slyšeli pouze část. Nezaměřujete se na dokonaný děj.

Po těchto slovesech nelze použít infinitiv s TO.

Seznamy sloves

Jelikož již znáte problematiku infinitivů a gerundií, je na čase seznámit se s nejdůlěžitými slovesy z obou kategorií.

U sloves, která se pojí s infinitivem i gerundiem je poznámka:

hvězdička (*) = nedochází ke změně ve významu

křížek (+) = dochází ke změně ve významu, nebo použití

Slovesa, po kterých následuje infinitiv:

| afford |

convince |

intend* |

regret+ |

| advise* |

continue* |

learn |

remember+ |

| agree |

dare |

like+ |

remind |

| allow* |

decide |

long |

require |

| appear |

deserve |

love* |

seem |

| arrange |

enable |

manage |

start* |

| ask |

encourage |

mean+ |

struggle |

| attempt* |

expect |

need+ |

swear |

| (be) able |

fail |

offer |

teach |

| beg |

forbid |

order |

tell |

| begin* |

force |

permit |

threaten |

| care |

forget+ |

persuade |

trouble |

| choose |

happen |

plan |

try+ |

| cause |

hate+ |

prefer* |

urge |

| challenge |

help |

prepare |

volunteer |

| can't bear* |

hesitate |

pretend |

wait |

| choose |

hire |

propose* |

want |

| claim |

hope |

promise |

warn |

| consent |

instruct |

refuse |

wish |

Slovesa, po kterých následuje gerundium:

| admit |

deny |

involve |

recall |

| advise* |

detest |

keep |

recollect |

| allow* |

dislike |

like+ |

recommend |

| anticipate |

endure |

love* |

regret+ |

| appreciate |

enjoy |

mention |

remember+ |

| avoid |

escape |

mean+ |

resent |

| attempt* |

excuse |

mind |

resist |

| begin* |

fancy |

miss |

risk |

| can't bear* |

finish |

need+ |

start* |

| can't help |

forget+ |

permit* |

stop |

| consider |

forgive |

postpone |

suggest |

| contemplate |

hate+ |

practise |

try+ |

| continue* |

imagine |

prefer* |

understand |

| delay |

intend* |

propose* |

(be) worth |

Pozn.: Frázová slovesa v těchto seznamech nejsou obsažena, ale pochopitelně platí stejné pravidlo i pro ně, např:

He continued / carried on / went on speaking.

She postponed / put off leaving until tomorrow.

infinitiv a gerundium – zápor

Pokud chcete vyjádřit záporný infinitiv nebo gerundium, je anglická gramatika naštěstí jednoduchá: Před infinitiv nebo gerundium vložíte záporku NOT:

He pretended to know the answer.

He pretended not to hear.

I regret calling him.

I regret not calling him.

ZÁVĚR

Co napsat závěrem. Pokud jste dočetli až sem (a nepřeskakovali), tak vám jde jistě hlava kolem.

Zde platí to, co u každého gramatického jevu. Začít pomalu od začátku, protože naráz se to nedá vše zvládnout.

Obzvláště tato gramatika, protože se týká všech anglických sloves (samozřejmě tady nejsou napsána všechna slovesa, ale je tu již slušná slovní zásoba) a je zbytečné učit se slovní vzorec ke slovesu, které zatím moc neznám.

Ale pokud se budu učit nové sloveso, je ideální naučit se také rovnou jeho správné spojení s dalším slovesem. Určitě je dobré vědět základní spojení, která jsou zmíněna hned v úvodu. A pak, až se budete učit další nová slovesa a budete je používat, je dobré občas se mrknout na tuto gramatiku.

V budoucnosti máme v plánu se ke gramatice slovesných vzorců vracet ve formě krátkých článků, které se budou zaměřovat hlavně na ta slovesa, se kterými se pojí infinitiv i gerundium a mění se tak jejich význam.

As your 1st term score is not very satisfying, I want you to make your reputation better,

therefore REVISE everything that concerns:

NOUNS, ADJECTIVES, ADVERBS, PRONOUNS

in ENGLISH FILE Pre-Intermediate and Intermediate, GRAMMAR BANK.

Writing section - page 119/A letter or email of complaint, ex. c, d

We did Vocabulary bank page 163, Grammar bank page 146.

1. GRAMMAR BANK page 147 / Learn grammar rules how to use gerunds and infinitives. Focus on COMMON VERBS which take the gerund/which take the infinitive

2. VOCABULARY BANK page 161, Learn vocabulary and articles about education in the UK and In the US

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_14.htm

http://www.englishpage.com/gerunds/gerunds_infinitives_21.htm

| |

Verb Lists: Infinitives and Gerunds

|

| Principles of Composition |

|

Verbs Followed by an Infinitive

She agreed to speak before the game. |

agree

aim

appear

arrange

ask

attempt

be able

beg

begin

care

choose

condescend |

consent

continue

dare

decide

deserve

detest

dislike

expect

fail

forget

get

happen |

have

hesitate

hope

hurry

intend

leap

leave

like

long

love

mean

neglect |

offer

ought

plan

prefer

prepare

proceed

promise

propose

refuse

remember

say |

shoot

start

stop

strive

swear

threaten

try

use

wait

want

wish |

Verbs Followed by an Object and an Infinitive

Everyone expected her to win. |

advise

allow

ask

beg

bring

build

buy

challenge |

choose

command

dare

direct

encourage

expect

forbid

force |

have

hire

instruct

invite

lead

leave

let

like |

love

motivate

order

pay

permit

persuade

prepare

promise |

remind

require

send

teach

tell

urge

want

warn |

Note: Some of these verbs are included in the list above

and may be used without an object. |

Verbs Followed by a Gerund

They enjoyed working on the boat. |

admit

advise

appreciate

avoid

can't help

complete

consider |

delay

deny

detest

dislike

enjoy

escape

excuse |

finish

forbid

get through

have

imagine

mind