Vážení študenti,

keďže ste žiakmi strednej školy a vyžaduje sa od vás určitá miera samostatnosti, na mojich stránkach, vždy pod záložkou vašej triedy nájdete svoje domáce úlohy aj gramatiku.

V prípade, že potrebujete niečo poslať elektronickou poštou, používajte nasledovný e-mail: katarina.privoznikova@gmail.com

Písomky sa dopisujú vždy len v stredu!!!!!!!!!!

I am truly sorry you found some unpleasant x-es in your IZK but that is the way things are. Do not want me to remind you that you have to come and take the test no matter what reasons for your absence in my lesson were. Three weeks is just enough time for you to learn, revise, prepare, come and take the test. I cannot wait more than three weeks until you bless me with your presence

SKVELÝ SLOVNÍK S BRITSKOU AJ AMERICKOU VÝSLOVNOSŤOU http://oxforddictionaries.com/

UČEBNICA https://elt.oup.com/student/englishfile/preint3/grammar/?cc=sk&selLanguage=sk

SLOVNÍK K UČEBNICI - the dictionary goes with your book. please, feel free to use it, just click on the link below

There comes the link: EF_3e_Pre-int_Slovak_WL.pdf

v prípade potreby uvádzam svoju mailovú adresu: katarina.privoznikova@gmail.com

SLOVNÍK K UČEBNICI ENGLISH FILE PRE-INTERMEDIATE - DICTIONARY Please, feel free to use it, if you don't know what a word in your book means, please, consult your dictionary.Just click on the link below

homework

Raymond-Murphy---English-grammar-in-use(1).pdf

Homework March 24th - 27th

Homework March 24th - deadline March 25th midday - poludnie

1. check your present perfect vs past simple exercises based on the key I have sent you to bour FB group and send me the picture of the exercises checked as a private message on Messenger.

4. SB 133 ex 4C a, b, c

5 WB p. 28 ex. 1a, 1b

6. WB p. 26 ex 1a, 1b

NEURČITÉ ZÁMENÁ

Neurčité zámená sa nevzťahujú ku konkrétnej osobe, miestu alebo veci. V angličtine existuje konkrétna skupina neurčitých zámen, ktoré sa vytvárajú použitím číslovky alebo distributívu, ktoré predchádza any, some, every a no.

| |

Osoba |

Miesto |

Vec |

| Všetko |

everyone

everybody |

everywhere |

everything |

| Časť (pozitívne) |

someone

somebody |

somewhere |

something |

| Časť (negatívne) |

anyone

anybody |

anywhere |

anything |

| Žiadne |

no one

nobody |

nowhere |

nothing |

Neurčité zámená použité so some a any zvyčajne popisujú neurčité alebo neúplné číslovky rovnakým spôsobom, ako keď sa some a any používajú samostatne.

Neurčité zámená sa vo vete umiestňujú na tú istú pozíciu ako podstatné mená.

| Podstatné meno |

Neurčité zámeno |

| I would like to go to Paris this summer. |

I would like to go somewhere this summer. |

| Jim gave me this book. |

Someone gave me this book. |

| I won't tell your secret to Sam. |

I won't tell your secret to anyone. |

| I bought my school supplies at the mall. |

I bought everything at the mall. |

KLADNÉ VETY

V kladných vetách neurčité zámená s použitím some sa využívajú pre vyjadrenie neurčitého množstva, neurčité zámená s every sa používajú pre vyjadrenie určitého množstva a zámená s no sa používajú pre vyjadrenie absencie. Neurčité zámená s no sa zvyčajne používajú v pozitívnych vetách s negatívnym zmyslom, ale nejedná sa pritom o negatívne vety, pretože im chýba slovo not.

PRÍKLADY

- Everyone is sleeping in my bed.

- Someone is sleeping in my bed.

- No one is sleeping in my bed.

- I gave everything to Sally.

- He saw something in the garden.

- There is nothing to eat.

- I looked everywhere for my keys.

- Keith is looking for somewhere to live.

- There is nowhere as beautiful as Paris.

Any a neurčité zámená vytvorené s jeho použitím môžu byť tiež použité v kladných vetách so smyslom podobným ku every: akákoľvek osoba, akékoľvek miesto, akákoľvek vec, atď.

PRÍKLADY

- They can choose anything from the menu.

- You may invite anybody you want to your birthday party.

- We can go anywhere you'd like this summer.

- He would give anything to get into Oxford.

- Fido would follow you anywhere.

ZÁPORNÉ VETY

Záporné vety môžu byť vytvorené jedine s neurčitými zámenami obsahujúcimi any.

PRÍKLADY

- I don't have anything to eat.

- She didn't go anywhere last week.

- I can't find anyone to come with me.

Mnohé záporné vety, ktoré obsahujú neurčité zámeno s any môžu byť zmenené na kladné vety so záporným zmyslom použitím neurčitého zámena s no. Avšak touto transformáciou dochádza aj ku zmene významu: veta, ktorá obsahuje neurčité zámeno s no je silnejšia a môže zahrňovať emocionálny kontext, ako defenzívnosť, beznádej, hnev, atď.

PRÍKLADY

- I don't know anything about it. = neutral

- I know nothing about it. = defensive

- I don't have anybody to talk to. = neutral

- I have nobody to talk to. = hopeless

- There wasn't anything we could do. = neutral

- There was nothing we could do. = defensive/angry

ZÁPORNÉ OTÁZKY

Neurčité zámená s every, some, a any môžu byť použité na vytvorenie negatívnych otázok. Na tieto otázky sa zvyčajne dá odpovedať "'áno" alebo "nie".

Zámená vytvorené s any a every sú používané k vytvoreniu skutočných otázok, zatiaľ čo tie so some sa vo všeobecnosti používajú pri otázkach, ktorých odpoveď poznáme alebo tušíme.

PRÍKLADY

- Is there anything to eat?

- Did you go anywhere last night?

- Is everyone here?

- Have you looked everywhere?

Tieto otázky sa môžu zmeniť na nepravé alebo rétorické otázky tým, že z nich spravíme záporné. Keď človek pokladá otázku tohto typu, očakáva odpoveď "nie".

PRÍKLADY

- Isn't there anything to eat?

- Didn't you go anywhere last night?

- Isn't everyone here?

- Haven't you looked everywhere?

Some a zámená s ním použité sú používané len v takých otázkach, o ktorých si myslíme, že vieme na ne odpovedať či otázky, ktoré nie sú skutočnými otázkami (pozvania, žiadosti, atď.) Osoba, ktorá sa pýta tieto otázky očakáva odpoveď "Áno".

PRÍKLADY

- Are you looking for someone?

- Have you lost something?

- Are you going somewhere?

- Could somebody help me, please? = request

- Would you like to go somewhere this weekend? = invitation

Tieto otázky sa dajú vytvárať ešte jednoznačnejšie, pokiaľ sú záporné. V tom prípade si je človek, ktorý ich kladie, úplne istý, že dostane odpoveď "Áno".

PRÍKLADY

- Aren't you looking for someone?

- Haven't you lost something?

- Aren't you going somewhere?

- Couldn't somebody help me, please?

- Wouldn't you like to go somewhere this weekend?

Homework Wednesday March 25th - deadline March 26th midday - poludnie

Streda 25. marec

1. Workbook p. 27 ex. 2 a, b – present perfect or past simple

2. Workbook p. 27 ex. 3 a – pronunciation

3. Workbook p. 27 ex. 4 listening

4. Workbook p. 27 - copy useful words and phrases into your exercise books and give their translation

5. Student´s book p. 32 ex. 1 Listening – 1a, 1b, 1c

Homework March 26th – deadline March 27th midday – poludnie

Štvrtok 26. Marec

1. Student´s book p. 32 ex. 4 READING 4a, 4b

2. Workbook p. 29 ex. 4 a, b - READING

3. Student´s book p. 33 ex. 5a/b – do zošita – do in your exercise books

Homework March 27th – deadline Saturday March 28th midday – poludnie

Piatok 27.marec

1. Workbook p. 29 ex. 5a, 5b – Listening

2. Workbook p. 29 - copy useful words and phrases to your exercise books and give their translation

3. Watch this video about ed/ing adjectives https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4J9vt7dbdvs

4. Student´s book p. 33 ex. 6a, b

5. Workbook p. 28 ex 2

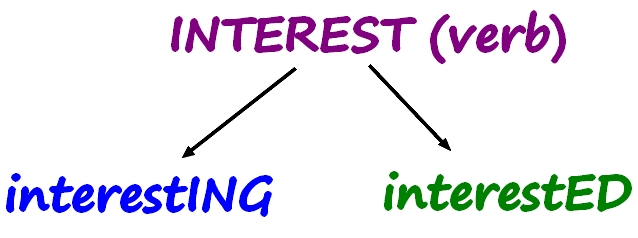

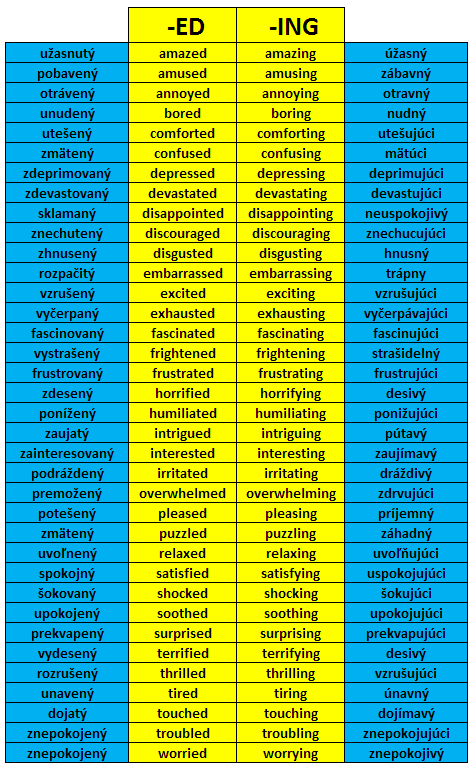

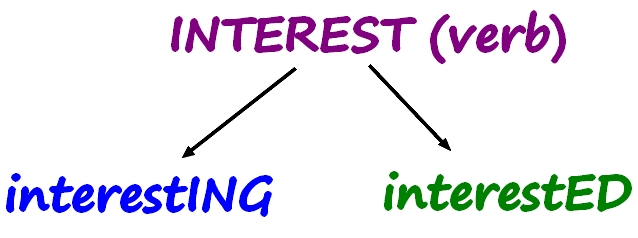

V angličtine vieme z niektorých slovies vytvoriť prídavné mená s koncovkou ‘-ing‘ alebo ‘-ed‘.

Takýmito slovesami sú napr.:

- AMAZE

- ANNOY

- ASTONISH

- FRIGHTEN

- EXCITE

- BORE

- TIRE

- EXHAUST

- INTEREST

Takto vytvorené prídavné mená nevyjadrujú to isté. Napr. príd. meno INTERESTING nemôžeme voľne zamieňať s príd. menom INTERESTED.

‘-ing’ adjectives

- He’s an interesting singer.

- an annoying habit

‘-ing‘ prídavné mená opisujú charakter podmetu (= vyjadrujú vlastnosti vecí, osôb, dejov).

- It was an amazing trip. -> Aký bol ten výlet? Za aký ho pokladám? Ako ho viem vlastnosťami charakterizovať? (= bol jednoducho skvelý)

- an interesting film -> Aká je charakteristická črta filmu? Aký ten film je? (= zaujímavý)

‘-ed’ adjectives

- I am frightened of spiders.

- I am shocked.

‘-ed‘ prídavné mená opisujú pocity podmetu (= ako sa cíti / čo vnútorne prežíva / aký má k niečomu postoj).

- I am interested in hockey. -> Aký postoj zaujímam voči hokeju? (= hokej ma zaujíma)

- I am bored. -> Ako sa cítim? Čo vnútorne prežívam (= som znudený)

ZOZNAM

najbežnejších dvojíc prídavných mien na -ed a -ing:

Veľmi všeobecne povedané majú prídavné mená na –ed v SJ koncovku –ný,

a tie, ktoré sa končia na –ing, sa v SJ končia na –ci. Nie vždy to však platí.

VIDEÁ:

Homework March 9th - March 13th

domáce úlohy som vám podrobne vysvetlené poslala prostredníctvom správy v aplikácii edupage.

Predprítomný čas (present perfect) – stavba, použitie. Rozdiel predprítomný čas a minulý čas, rozdiel predprítomný čas a prítomný čas jednoduchý. Viac sa dočítate v článku.

Predprítomný čas (present perfect) – stavba, použitie. Rozdiel predprítomný čas a minulý čas, rozdiel predprítomný čas a prítomný čas jednoduchý. Viac sa dočítate v článku.

Základná stavba

| KLADNÁ VETA |

| Podmet + pomocné sloveso HAVE / HAS + minulé príčastie plnovýznamového slovesa (tretí tvar) |

He, she, it + has + worked

I, you, we, they + have + worked |

| She has worked as a teacher since 2000. |

| ZÁPORNÁ VETA |

| Podmet + have / has + záporný výraz NOT + minulé príčastie plnovýznamového slovesa (tretí tvar) (HAS NOT vytvára skrátený tvar HASN’T / HAVE NOT vytvára skrátený tvar HAVEN’T) |

He, she, it + has + not + worked

I, you, we, they + have + not + worked |

| She hasn’t worked as a teacher since 2000. |

| OTÁZKA |

| Have / has + podmet + minulé príčastie plnovýznamového slovesa (tretí tvar) |

Has + he, she, it + worked

Have + I, you, we, they + worked |

| Has she worked as a teacher since 2000? |

Všimnite si skrátené tvary pomocných slovies HAVE / HAS v kladnej vete a zápore:

I have worked = I‘ve worked

I have not worked = I haven’t worked |

He has worked = He‘s worked

He has not worked = He hasn’t worked |

Skrátený tvar ” ‘s ” pripojený k podmetu nemusí mať v anglickej vete vždy význam pomocného slovesa HAS. Sloveso v minulom príčastí nám pomôže určiť, že ide práve o skrátený tvar od pomocného slovesa HAS. Porovnajte:

She is a teacher.

She has worked as a teacher for ten years. |

She’s a teacher.

She’s worked as a teacher for ten years. |

Použitie

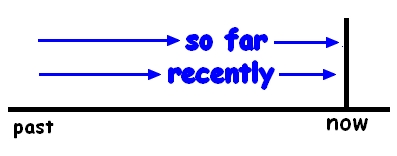

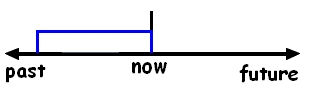

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS používame vtedy, ak hovoríme o dejoch (najmä stavoch), ktoré začali v minulosti a naďalej pokračujú alebo trvajú v prítomnosti.

- I’ve known John since 2005. (= dej začal v roku 2005 a stále trvá)

- I’ve worked in this recording studio for two months. (= dej začal pred dvoma mesiacmi a stále trvá)

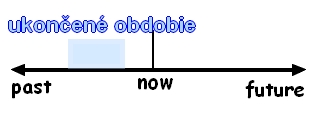

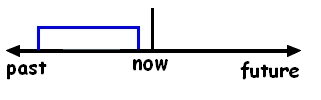

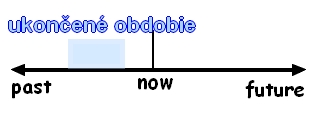

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS používame rovnako vtedy, ak hovoríme o dejoch, ktoré sa už niekedy v minulosti odohrali, ale ešte stále sa môžu odohrať v budúcnosti. Časové obdobie, na ktorom sa dej už predtým odohral neskončilo (hovoriaci ho považuje za neukončené). Dej sa mohol v minulosti odohrať nie len raz.

- I’ve been to Mexico many times. (= stále žijem, môj život stále trvá, preto je možné, že sa do Mexika ešte môžem dostať)

- J.K. Rowling has written a lot of books. (= spisovateľka stále žije, stále môže niečo napísať)

Časový údaj naznačujúci neukončené obdobie môže byť vo vete vyjadrené priamo:

-

- Have you seen John this morning? (= stále je ráno)

- I haven’t watched TV today. (= stále je dnešok)

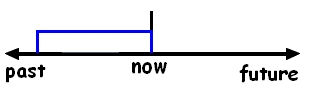

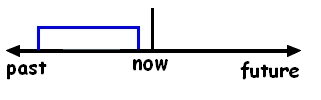

Ak časový výraz vo vete naznačuje ukončené obdobie, používame minulý čas. Ak naznačuje obdobie neukončené, používame predprítomný čas.

-

- Have you met him this morning? – obdobie THIS MORNING ešte neskončilo, teda ešte stále je RÁNO a teda dej sa počas daného obdobia môže znova odohrať / pozmeniť

- Did you meet him this morning? – obdobie THIS MORNING už skončilo, je napr. popoludnie, večer a teda dej sa počas daného obdobia nemôže znova odohrať / pozmeniť

Do modrého obdĺžnika v obrázkoch si môžete dosadiť aj iné časové údaje ako v nasledujúcich vetách. Niekoľko príkladov:

-

-

-

- It didn’t snow yesterday. – YESTERDAY (= ukončené obdobie)

- It was very hot last week. – LAST WEEK (= ukončené obdobie)

- I was very patient when I was a child. – WHEN I WAS A CHILD (= ukončené obdobie)

- She did her homework five minutes ago. – FIVE MINUTES AGO (= ukončené obdobie)

- He kissed me on Monday. – ON MONDAY (= ukončené obdobie)

- I worked here for twenty years. – minulý čas naznačuje ukončené obdobie, teda v prítomnosti tu už nepracujem

-

-

-

- It hasn’t snowed today. – TODAY (= neukončené obdobie – dnešok stále TRVÁ)

- I have worked here for twenty years. – predprítomný čas naznačuje neukončené obdobie, teda v súčasnosti tu stále pracujem

- Sarah hasn’t done very well so far. – SO FAR (= neukončené obdobie)

- I haven’t seen Lisa this afternoon. – THIS AFTERNOON (= neukončené obdobie)

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS používame rovnako vtedy, ak hovoríme o aktuálnych udalostiach (napr. správy / novinky), kde sa dôraz kladie na danú udalosť, ktorú hovoriaci vníma ako istý fakt v prítomnosti. V týchto vetách sa nenachádza presný časový údaj.

Ak pokračujeme v rozprávaní o tejto novinke (hovoríme o bližších detailoch týkajúcich sa deja ako napr. čas / príčina apod.), používame minulý čas jednoduchý.

- Have you heard? The prime minister has been shot by an old man. He was shot because he was outside a shop without his bodyguards.

- A: Ow! I‘ve cut myself shaving. ≈ B: How did you do that?

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS používame rovnako vtedy, ak hovoríme o početnosti / frekvencii deja počas neukončeného obdobia. Pri ukončenom období, použijeme minulý čas.

- How long did you work in these conditions? – Ako dlho si pracoval v tých podmienkach? (= už tam nepracuje)

- How long have you worked in these conditions? – Ako dlho (už) pracuješ v tých podmienkach? (= stále tam pracuje)

- How many books did Shakespeare write? – je mŕtvy, viac kníh už nenapíše

- How many books has J.K. Rowling written? – žije, stále môže nejaké napísať

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS používame ďalej vtedy, ak vyjadrujeme ľudskú skúsenosť s nejakým dejom (hovoríme o tom, čo človek zažil / nezažil doteraz) a človek stále žije. Ak je človek mŕtvy a my o jeho skúsenostiach rozprávame, musíme použiť minulý čas.

- I have been to London.

- I have never had a lot of money.

V tomto použití sa často nachádzajú frázy ako This is the first / second time…, po ktorých umiestňujeme predprítomný čas.

-

- This is the first time I have eaten snails.

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS používame rovnako vtedy, ak hovoríme o deji, ktorý sa celý odohral v minulosti, ale dôraz sa kladie na jeho výsledok alebo vplyv na prítomnosť. Tento dej má spojitosť s prítomnosťou.

- A: “Where is your book?” ≈ B: “Someone has stolen it.“

- A: “Is Peter at home?” ≈ B: “No, he has gone out.“

- The lift has broken down. (Výťah sa pokazil. Vplyv na prítomnosť = napr. musíme ísť pešky)

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS môžeme upresniť s nasledujúcimi príslovkami. V týchto vetách hovoríme o tom, čo sa stalo doteraz alebo práve naopak, čo sa do teraz nestalo. Toto je typický príklad, keby používame predprítomný čas.

- I’ve already seen it. – Už som to videl.

- Has he come yet? – Už prišiel?

- My brother hasn’t returned yet. – Môj brat sa ešte nevrátil.

- She still hasn’t got over her death. - Ešte stále sa nespamätala z jej smrti.

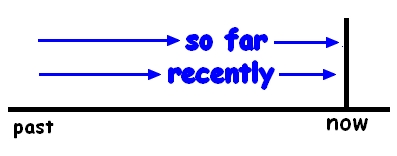

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS často používame aj s ostatnými príslovkami, ktoré nám popisujú obdobie, ktoré začalo v minulosti a stále trvá.

- Have you met him recently?

- I’ve recently bought him lunch. – Nedávno (v poslednej dobe) som mu kúpil obed.

- Have you visited the Czech Republic lately? – Navštívil si Česko nedávno? (nedávna minulosť)

- I’ve been away for a long time. – Som dlho preč.

- She has eaten a lot of food in the last few days. – V posledných dňoch je veľa.

- We haven’t made a lot of mistakes so far. – Doteraz sme neurobili veľa chýb.

- Up to now he has been successful. – Doteraz bol úspešný.

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS je typický aj pre frekvenčné príslovky ako napr. always, often apod., ak popisujú obdobie, ktoré sa neskončilo – stále trvá.

- I have always wanted to go abroad. – Stále som chcel ísť do zahraničia. (= obdobie ešte neskončilo – pretože ja chcem ísť ešte stále aj v prítomnosti)

MINULÝ ČAS vs. PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS

ČASOVÝ ÚDAJ

ČASOVÝ ÚDAJ

Minulý čas používame vtedy, ak hovoríme o dejoch, ktoré sa odohrali v určitom čase v minulosti, ktorý je vo vete priamo uvedený, všeobecne známy, nepriamo vyjadrený alebo z kontextu jasný.

- J. K. Rowling wrote her first book in 1971. (Kedy? V roku 1971 = čas je uvedený)

Predprítomný čas používame vtedy, ak hovoríme o dejoch, ktoré sa odohrali v neurčitom čase v minulosti. Presný čas je v tomto prípade neznámy alebo pre hovoriaceho nepodstatný, no obdobie, počas ktorého sa tieto deje mohli a ešte môžu odohrať považujeme za neukončené.

- J. K. Rowling has written a lot of books. (Kedy? Nevieme. Presný čas nie je spomenutý. Autorka žije, stále môže napísať ďalšie knihy.)

Deje vyjadrené minulým časom nemajú spojitosť s prítomnosťou. Nie je však pravda, že vždy, ak vo vete nie je presný čas používame predprítomný čas. Podstatný je stále KONTEXT, v ktorom sa nachádzame. Ak hovoríme o minuloročnej dovolenke, nemusíme v každej vete použiť príslovkové určenie, ktoré je typické pre minulý čas a aj napriek tomu vo vete použijeme minulý čas, lebo z kontextu je jasné, že ide o ukončený dej. Ako sme si vyššie spomínali, príslovkové určenie času vo vete nemusí byť vôbec vyjadrené, ak je známe z kontextu, hovoriaci aj poslucháč vzájomne poznajú okolnosti deja (kedy sa odohral), poprípade to je všeobecne známy fakt.

Ak napr. povieme o Shakespearovi, že napísal Hamleta, rovnako nepoužijeme predprítomný čas, pretože osoba, o ktorej hovoríme je mŕtva (a to aj napriek tomu, že vo vete nemáme zverejnený presný čas).

-

- Shakespeare wrote Hamlet.

UKONČENÉ / NEUKONČENÉ ČASOVÉ OBDOBIE

UKONČENÉ / NEUKONČENÉ ČASOVÉ OBDOBIE

Minulým časom hovoríme o ukončenom časovom období.

- He lived in New York for twenty years. (= už tam nežije, presťahoval sa alebo zomrel)

- I was a truck driver for ten years. (= ako vodič nákladiaku už nepracujem)

Predprítomným časom hovoríme o dejoch, ktoré pokračujú od nejakého času v minulosti až doteraz (= neukončené časové obdobie).

- He has lived in New York for twenty years. (= stále tam žije)

- I’ve been a truck driver for ten years. (= ešte stále pracujem ako vodič nákladiaku)

UKONČENÉ / NEUKONČENÉ ČASOVÉ OBDOBIE – ČASOVÉ VÝRAZY

UKONČENÉ / NEUKONČENÉ ČASOVÉ OBDOBIE – ČASOVÉ VÝRAZY

Minulý čas používame vo vetách, kde časový výraz uverejnený vo vete naznačuje ukončené obdobie. Dej sa na takomto časovom období nemôže odohrať znova.

- Did you meet him this morning? - obdobie THIS MORNING už skončilo, je napr. popoludnie, večer a teda dej sa počas daného obdobia nemôže znova odohrať / pozmeniť

Predprítomný čas používame vo vetách, kde časový výraz uverejnený vo vete naznačuje neukončené obdobie. Dej sa na takomto časovom období môže odohrať znova.

- Have you met him this morning? – obdobie THIS MORNING ešte neskončilo, teda ešte stále je RÁNO a teda dej sa počas daného obdobia môže znova odohrať / pozmeniť

MOŽNOSŤ DEJA ODOHRAŤ SA

MOŽNOSŤ DEJA ODOHRAŤ SA

Minulý čas používame vtedy, ak hovoríme o dejoch, ktoré sa v minulosti odohrali a už sa viac zopakovať nemôžu (čas je ukončený, aktér deja zomrel apod.)

- She once spoke to Karel Kryl. (= už sa s ním nemôžem porozprávať, zomrel)

Predprítomný čas používame naopak, ak sa dej, ktorý už niekedy prebehol môže zopakovať a uskutočniť znova (čas nie je ukončený, aktér deja žije apod.)

- She has spoken to J. K. Rowling. (= ešte sa s ňou môžem porozprávať, stále žije).

SUBJEKTÍVNY POHĽAD NA DEJ

SUBJEKTÍVNY POHĽAD NA DEJ

Hovoriaci sa môže niekedy na základe aktuálnej situácie rozhodnúť, či v niektorých situáciach použije minulý čas alebo predprítomný čas.

Minulý čas používame, ak hovoriaci nevníma spojitosť medzi dejom a prítomnosťou (udalosť je od prítomnosti vzdialená časovo alebo miestne).

- I lost my wallet at school. (= hovoriaci vníma udalosť ako vzdialenejší dej, čo sa času alebo miesta týka)

Predprítomný čas používame naopak, ak hovoriaci vníma spojitosť s prítomnosťou (udalosť nie je od prítomnosti vzdialená časovo alebo miestne).

- I have lost my wallet at school. (= hovoriaci vníma udalosť ako aktuálny dej, čerstvý dej a je napr. blízko školy)

VÝSLEDOK DEJA

VÝSLEDOK DEJA

Minulý čas používame vtedy, ak dej, ktorý prebehol v minulosti nemá dopad na prítomnosť – na prítomnosť nemá žiadne následky.

- I broke my hand but it’s fine now. (= udalosť v minulosti)

Predpítomný čas používame vtedy, ak dej, ktorý prebehol v minulosti má dopad na prítomnosť – vidíme jeho následky.

- I’ve broken my hand. (= stále ju nemám vyliečenú, ešte stále sa mi zotavuje)

Porovnajte:

- The supermarkets have just opened. (= TERAZ sú otvorené) – predprítomný čas nám hovorí niečo ohľadom prítomnosti

- The supermarkets opened last month. They’re doing well. – minulý čas s presným časovým údajom v minulosti (= LAST MONTH)

- The supermarkets opened last month. Then they closed again five weeks later. – minulý čas nám nehovorí nič ohľadom prítomnosti

PREDPRÍTOMNÝ ČAS vs. PRÍTOMNÝ ČAS

Hlavný rozdiel medzi prítomným časom a predprítomným časom je v tom, či sa dej týka iba prítomnosti alebo má dej istú súvislosť s minulosťou.

- I am a waiter. – Som čašník. (= touto vetou popisujeme iba aktuálne dianie)

- I have been a waiter for five years. – Som čašníkom už 5 rokov. (= touto vetou popisujeme aj aktuálny stav, ale zohľadňujeme pri tom aj trvanie deja spojené s minulosťou)

- I only know John by sight. – Poznám Johna iba z videnia. (= konštatujem iba prítomnosť)

- I have known John for years. – Poznám Johna už roky. (= pri konštatovaní prítomnosti zohľadňujem minulosť)

-

We are working / work for the BBC since 2005.We are working / work for the BBC for over ten years.- We have been working / have worked for the BBC since 2005 / for over ten years.

Homework, February 26th

relative pronouns, WB p 21 ex. 1

do not forget about your projects - deadline Monday March 2nd, follow the example in your workbooks, the tour of the magic triangle

Homework, February 4th

arports - vocabulary, spelling - the ones who stayed at school took a dictation

expressing future in English

learn the grammar

Článok venovaný budúcim časom v angličtine – WILL / BE GOING TO / PRESENT CONTINUOUS / PRESENT SIMPLE.

Článok venovaný budúcim časom v angličtine – WILL / BE GOING TO / PRESENT CONTINUOUS / PRESENT SIMPLE.

| WILL (budúci čas jednoduchý) |

ZÁKLADNÁ STAVBA

| KLADNÁ VETA |

| Podmet + WILL + infinitív plnovýznamového slovesa bez TO (WILL vytvára skrátený tvar ‘ll) |

| I, you, he, she, it, we, they + will + help |

| She will help us. |

| ZÁPORNÁ VETA |

| Podmet + WILL + záporný výraz NOT + infinitív plnovýznamového slovesa bez TO (WILL NOT vytvára skrátený tvar WON’T) |

| I, you, he, she, it, we, they + will + not + help |

| She won’t help us. |

| OTÁZKA |

| WILL + podmet + infinitív plnovýznamového slovesa bez TO |

| Will + I, you, he, she, it, we, they + help |

| Will she help us? |

Budúci čas (pomocné sloveso WILL) má vo všetkých osobách rovnaký tvar!

Budúci čas (pomocné sloveso WILL) má vo všetkých osobách rovnaký tvar!

Všimnite si skrátené tvary pomocného slovesa WILL v kladnej vete a zápore:

| She will help us = She‘ll help us. |

She will not help us = She won’t help us. |

ČISTÁ BUDÚCNOSŤ

Ak v angličtine informujeme ohľadom budúcnosti, bez vedľajších významových prvkov – len konštatujeme, čo sa udeje v budúcnosti – používame WILL. Najtypickejšie sú pre toto použitie “budúce fakty”. Tieto deje sa určite odohrajú a v silách hovoriaceho nie je ich zmeniť: Lepšie to pochopíte na nasledujúcich vetách:

- The sun will rise tomorrow.

- He will be thirty on Sunday.

- The baby will be born in August.

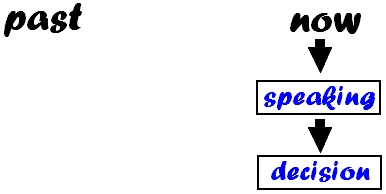

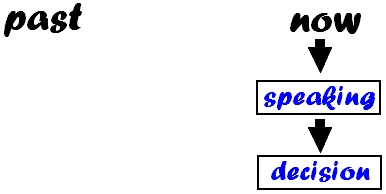

ROZHODNUTIE V MOMENTE ROZHOVORU

Ak sa hovoriaci rozhodol priamo v okamihu rozhovoru, jeho rozhodnutie nebolo vopred plánové, ale je to bezprostredná reakcia na aktuálne dianie – používame WILL. Takto sa WILL používa aj v baroch, reštauráciách, keď si objednávame jedlo, či pitie.

- A: ” What would you like to eat? “ ≈ B: ” I‘ll have the soup, please. “ - Hovoriaci “B” si vopred dať polievku neplánoval, rozhodol sa bezprostredne počas danej situácie

- A: “ I don’t know how to turn the TV on? ” ≈ B: ” Oh, it’s easy. I‘ll show you.“ - Nastal nepredvídateľný dej – hovoriaci “A” nevie zapnúť TV. Hovoriaci “B” sa preto v momente rozhovoru rozhoduje, že mu pomôže. Ide teda o okamžité rozhodnutie.

SUBJEKTÍVNA PREDPOVEĎ NEPODLOŽENÁ DÔKAZMI

Ak budúcnosť, o ktorej hovoriaci hovorí iba subjektívne predpovedá – sú to možno jeho očakávanie, nemá žiadne reálna dôkazy, ktoré by dokázali, že dej skutočne prebehne presne tak ako hovoriaci (subjektívne) predpovedá.

- I’m sure she will love teaching French in London.

- She hasn’t answered the phone today. I expect she will come this afternoon.

- I think it will rain on Sunday.

Vety, ktoré o takýchto predpovediach nepodložených dôkazmi pojednávajú často uvádzajú tieto frázy:

- I expect - I expect she will come this afternoon.

- (be) afraid

- (be) sure

- surely – It will surely pay. – Určite sa to vyplatí

- (I) think

- (I) don’t think

- I suppose

- probably – She will probably be there.

OCHOTA

WILL často používame vo vetách, ktoré vyjadrujú ochotu pomôcť. Hovoriaci sa ponúka pomôcť.

- A: ” That TV looks heavy. ” ≈ B: ” I will help you with it. “ (= I am willing to help you)

- A: “ That TV looks heavy. “ ≈ B: “

I help you with it. “

NEOCHOTA

WON’T (zápor od WILL) používame vo význame neochoty, či dôrazného odmietnutia. Podmetom týchto odmietnutí je živá bytosť.

-

- I won’t tolerate that. / I will not tolerate that. – To nestrpím. (= I am not willing to tolerate that.)

Takéto vety často prekladáme dvojitým záporom “nie a nie“, teda “nechce, odmieta” napr. naštartovať / povedať / počúvať apod.

-

- I’d like to give him a hand but he won’t tell the truth. – Chcel by som mu pomôcť, ale on nie a nie a povedať pravdu. (nechce povedať pravdu)

WON’T (zápor od WILL) často používame aj vtedy, ak podmetom nie je osoba (napr. človek).

-

- The bus won’t start. – Ten autobus nie a nie naštartovať. (nechce naštartovať)

Ďalšie typické situácie, kde používame WILL:

| SĽUB

- (I promise) I won’t tell anyone.

ZDVORILÁ PROSBA

- Will you help us, please? / Will you open the window, please?

POZVANIE

ZDVORILÝ POKYN

- Will you be quiet? (= Buďte ticho.)

VYHRÁŽKA, UPOZORNENIE

- I will kill you if you tell her about it

|

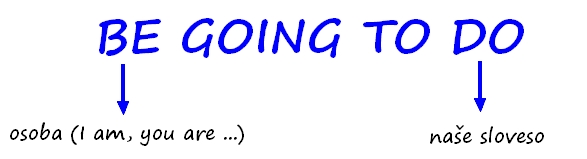

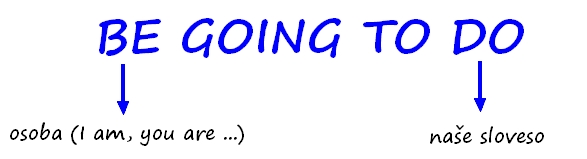

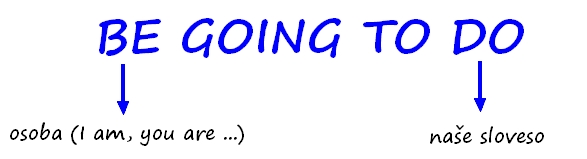

ZÁKLADNÁ STAVBA

ZÁPOR tvoríme pridaním záporu “NOT” k osobe – napr. I am not going to do, you are not going to do atd.

OTÁZKU tvoríme prehodením slovosledu osoby – napr. Are you going to do …?, is he going to do …?

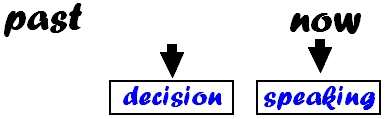

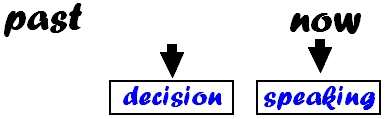

ÚMYSLY – PLÁNOVANÁ BUDÚCNOSŤ

BE GOING TO používame pre také budúce deje, ktoré už v momente, keď hovor prebieha máme dávno premyslené, naplánované. V momente rozhovoru sú tieto deje už našimi plánmi, úmyslami apod.

- We are going to build our own hotel. – V momente, kedy o tejto udalosti hovoríme ju máme už dávno naplánovanú – oznamujeme iba, čo sa chystáme urobiť, čo máme v pláne urobiť.

- I am going to call her. – Mám v pláne jej zavolať.

V takýchto vetách nemusíme spomínať ani osobu, ktorá má v pláne niečo urobiť. Použijeme jednoducho trpný rod s BE GOING TO.

-

- The hotel is going to be built.

Ak po BE GOING TO nasledujú slovesá GO / COME je vhodnejšie použiť prítomný priebehový čas namiesto BE GOING TO GO / BE GOING TO COME.

-

- ” I am going to England …” je častejšie používaná verzia ako “ I am going to go to England “. Verzia s GOING TO nie je však nesprávna, iba menej používaná.

PREDPOVEĎ PODLOŽENÁ DÔKAZMI

BE GOING TO používame rovnako vtedy, ak hovoríme o predpovedi, ktorú máme podloženú dôkazmi. Hovoriaci ich má počas rozhovoru k dispozícií, aby sa na ne mohol odvolať (nap. niečo čo vidí, počuje, niečo vyplýva zo situácie apod.)

- Look at those clouds! It is going to snow. – Nie je to iba subjektívna predpoveď, ale predpoveď podložená dôkazmi – vidíme na oblohe strašne veľa napr. čiernych mrakov, je teda isté, že bude snežiť a možno už nejaká vločka aj spadla.

- It sounds like the plane’s going to take off.

BE GOING TO väčšinou hovorí o dejoch, o ktorých už v momente rozhovoru máme nejakú predstavu, o ktorých sme premýšľali, ktoré chystáme, ale ešte sme ich úplne nezariadili. BE GOING TO vyjadruje teda nejaký “úmysel v budúcnosti“, alebo niečo, čo sme sa rozhodli urobiť, ale ešte nezariadili. Je to teda iba úmysel, ktorý sa môže zmeniť.

PRESENT CONTINUOUS väčšinou hovorí o dejoch, ktoré sa stanu 100%, pretože všetko máme už zariadené. V týchto vetách býva príslovkové určenie času častejšie ako pri BE GOING TO. PRESENT CONTINUOUS teda používame, keď už máme všetko naplánované na určitý čas / miesto v budúcnosti a nebudeme to meniť.

- They are going to ged married in two months. (= They have already decided to do it.)

- They are getting married next month. (= They have decided and arranged to do it.)

Často sa však stáva, že v tomto význame naplánovaných dejov tieto vyjadrenia budúcnosti môžeme zamieňať. Kedy PRESENT CONTINUOUS vo vyjadrení budúcnosti zameniť za BE GOING TO rozhodne nemôžeme?

Ak hovoríme o predpokladoch založený na dôkazoch, vtedy môžeme použiť iba BE GOING TO.

- Look at those clouds! It is going to snow.

| PRESENT CONTINUOUS (prítomný čas priebehový) |

ZÁKLADNÁ STAVBA

Základnú stavbu nájdete v článku venovanému PRESENT CONTINUOUS (viac TU)

PLÁNOVANÁ BUDÚCNOSŤ

PRESENT CONTINUOUS (čas prítomný priebehový) s budúcim významom používame pre také deje, ktoré sú naplánováné / zariadené.

- What time are you leaving tomorrow?

- I am going to the party this evening.

| PRESENT SIMPLE (prítomný čas jednoduchý) |

ZÁKLADNÁ STAVBA

Základnú stavbu nájdete v článku venovanému PRESENT SIMPLE (viac TU)

ROZVRH, PROGRAM, KALENDÁR…

PRESENT SIMPLE (prítomný čas jednoduchý) s budúcim významom hovorí o dejoch, ktoré sa v budúcnosti majú odohrať podľa nejakého rozpisu, programu, kalendára, cestovného poriadku apod.

- The film starts at 11.

- The library closes at 6.30 p.m.

- When does the bus leave?

WILL vs. GOING TO

NEPLÁNOVANÁ BUDÚCNOSŤ (= rozhodneme sa v momente rozhovoru)

Rozhodnutie padne ako reakcia na práve odohrávajúci sa dej v momente rozhovoru → WILL

- I like this coat. I think I‘ll buy it

- A: What would you like to eat? B: I‘ll have a pizza, please.

PLÁNOVANÁ BUDÚCNOSŤ (= rozhodli sme sa niečo urobiť už pred rozhovorom)

V momente rozhovoru sme už rozhodnutí o tom, že niečo urobíme → BE GOING TO

- I am going to clean my room this afternoon. (= I decided to clean it this morning.)

|

| PREDPOVEĎ V BUDÚCNOSTI NEPODLOŽENÁ DÔKAZMI (= subjektívna) → WILL

- I’m sure you‘ll enjoy the film.

- I’m sure it won’t rain tomorrow. It‘ll be another beautiful, sunndy day.

PREDPOVEĎ V BUDÚCNOSTI PODLOŽENÁ DÔKAZMI → BE GOING TO

- He’s running towards the goal, and he‘s going to score.

|

Nadobudnuté vedomosti si môžete otestovať v krátkom teste:

test 1 https://www.englishguide.sk/test-1-will-vs-be-going-to/

test 2 https://www.englishguide.sk/test-2-will-vs-be-going-to/

Homework, January 23rd

learn the article At the airport you find in your Workbooks, p. 17, unit 3A, I am going to examine you on Tuesday next week.

Please, revise the form and usage of BE GOING TO structure for future plans and predictions, Woorkbooks, p. 17 ex 1 a, 1b - do the exercises for your homework

ZÁKLADNÁ STAVBA

ZÁPOR tvoríme pridaním záporu “NOT” k osobe – napr. I am not going to do, you are not going to do atd.

OTÁZKU tvoríme prehodením slovosledu osoby – napr. Are you going to do …?, is he going to do …?

ÚMYSLY – PLÁNOVANÁ BUDÚCNOSŤ

BE GOING TO používame pre také budúce deje, ktoré už v momente, keď hovor prebieha máme dávno premyslené, naplánované. V momente rozhovoru sú tieto deje už našimi plánmi, úmyslami apod.

- We are going to build our own hotel. – V momente, kedy o tejto udalosti hovoríme ju máme už dávno naplánovanú – oznamujeme iba, čo sa chystáme urobiť, čo máme v pláne urobiť.

- I am going to call her. – Mám v pláne jej zavolať.

V takýchto vetách nemusíme spomínať ani osobu, ktorá má v pláne niečo urobiť. Použijeme jednoducho trpný rod s BE GOING TO.

-

- The hotel is going to be built.

Ak po BE GOING TO nasledujú slovesá GO / COME je vhodnejšie použiť prítomný priebehový čas namiesto BE GOING TO GO / BE GOING TO COME.

-

- ” I am going to England …” je častejšie používaná verzia ako “ I am going to go to England “. Verzia s GOING TO nie je však nesprávna, iba menej používaná.

PREDPOVEĎ PODLOŽENÁ DÔKAZMI

BE GOING TO používame rovnako vtedy, ak hovoríme o predpovedi, ktorú máme podloženú dôkazmi. Hovoriaci ich má počas rozhovoru k dispozícií, aby sa na ne mohol odvolať (nap. niečo čo vidí, počuje, niečo vyplýva zo situácie apod.)

- Look at those clouds! It is going to snow. – Nie je to iba subjektívna predpoveď, ale predpoveď podložená dôkazmi – vidíme na oblohe strašne veľa napr. čiernych mrakov, je teda isté, že bude snežiť a možno už nejaká vločka aj spadla.

- It sounds like the plane’s going to take off.

BE GOING TO väčšinou hovorí o dejoch, o ktorých už v momente rozhovoru máme nejakú predstavu, o ktorých sme premýšľali, ktoré chystáme, ale ešte sme ich úplne nezariadili. BE GOING TO vyjadruje teda nejaký “úmysel v budúcnosti“, alebo niečo, čo sme sa rozhodli urobiť, ale ešte nezariadili. Je to teda iba úmysel, ktorý sa môže zmeniť.

PRESENT CONTINUOUS väčšinou hovorí o dejoch, ktoré sa stanu 100%, pretože všetko máme už zariadené. V týchto vetách býva príslovkové určenie času častejšie ako pri BE GOING TO. PRESENT CONTINUOUS teda používame, keď už máme všetko naplánované na určitý čas / miesto v budúcnosti a nebudeme to meniť.

- They are going to ged married in two months. (= They have already decided to do it.)

- They are getting married next month. (= They have decided and arranged to do it.)

Často sa však stáva, že v tomto význame naplánovaných dejov tieto vyjadrenia budúcnosti môžeme zamieňať. Kedy PRESENT CONTINUOUS vo vyjadrení budúcnosti zameniť za BE GOING TO rozhodne nemôžeme?

Ak hovoríme o predpokladoch založený na dôkazoch, vtedy môžeme použiť iba BE GOING TO.

- Look at those clouds! It is going to snow.

Homework December 9th

retell the article One October evening together with the sad ending

learn the prepositions of time and place at, in, on

Homework, November 27

p. 13, SB ex. 3c - answer the questions based on the tapescript you find o page 118 (1.35)

Homework, November 26th

copy both regular and irregular verbs from the article about holidays from your book to your exercise books, add base forms to irregular verbs

Homework, November 8th

Unit test next lesson, revise clothes, personality adjectives, present simple vs present continous, describing a picture, making complaint at a hotel, social phrases

Homework, October 28

description of a picture - usage of present continous, based on the tapescript which can be found after the main text in your SB, prepositions of place, the exercise below the painting by D. Hockney in your books.

Pls, learn and revise the rules of form and usage of present simple vs present continous. In case you did not take a test, come to see me to make a deal about your re-sits. It is always Wednesday after school. I cannot deprive you of the possibility of being taught and learn something new in your classes so you have to take the test in the afternoon

Homework, October 15th

learn the rules for present simple usage and form, pls, do ex. 1B b SB/ grammar bank into your exercise books

Homework, October 14th

who knows you beter - your mother or yur best friend? - learn the vocabulary, learn how to read and translate the article p. 6 SB

Homework, October 8th

pls, do the exercises 1a and 1b in your SB, grammar bank pages 127/128

Otázky v angličtině

Umět se ptát na otázky je velice praktické. Je to ale oblast, ve kterých spousta studentů pokulhává, a proto se dnes na tuto gramatiku zaměříme.

Rozdělení otázek

Otázky dělíme na dvě hlavní skupiny:

- Otázky zjišťovací (ano/ne)

- Otázky doplňovací (kde, kdy, jak, zač…)

Zjišťovací otázky mají stoupavou intonaci, a odpovědět na ně můžeme pomocí slov ANO / NE. Např. Máš rád guláš? Jsi odtud? Pracujete každý den? atd.

Doplňovací otázky mají klesavou intonaci a nelze na ně odpovědět samotným YES a NO. Začínají na tázací zájmeno, v angličtině tedy většinou na slova začínající na wh- (proto se jim někdy v angličtině říká WH- questions).

Tvoření otázek

Společným pravidlem pro většinu otázek je to, že se změní ve větě slovosled, a před podmět se dostává sloveso, přesně řečeno pomocné sloveso, nebo tzv. operátor.

Operátor je sloveso, ke kterému lze přidat NOT v záporu, a nebo může stát v otázkách před podmětem. Typickým příkladem takového operátoru je sloveso BÝT (to be).

Oznamovací věta: He is from Germany.

Tázací věta: Is he from Germany?  – slovosled se zde změnil, HE (podmět) a IS (sloveso BE – operátor) jsme prohodili.

– slovosled se zde změnil, HE (podmět) a IS (sloveso BE – operátor) jsme prohodili.

Mezi další operátory patří např. sloveso HAVE, CAN, WILL apod. Tedy:

I will – will I?

She has got- has she got?

They can – can they?

POZOR: Naprostá většina ostatních sloves NEJSOU operátory, nelze je tedy přesunout před podmět a nelze k nim v záporech ani přidávat NOT.

I go – go I? – I go not

She started – started she? – she startedn't

They work – work they? – they workn't

Proto je nutné si nějakým operátorem vypomoci. Pomocné sloveso, které v těchto případech používáme, je sloveso DO. Toto sloveso převezme všechny gramatické funkce (přesun před podmět v otázkách, přibírání NOT v záporech, koncovka -s ve třetí osobě, minulý čas apod.) a významové sloveso vždy zůstane v základním tvaru.

They like pizza.

Do they like pizza?

He works in Germany.

Does he work in Germany? – pomocné DO přibralo i koncovku pro třetí osobu jednotného čísla, významové sloveso WORK zůstává v základním tvaru!

POZOR: Sloveso DO se používá i jako významové sloveso, to se ale nedá použít jako operátor! Pokud potom tvoříme otázku na toto sloveso, bude ve větě jedno DO jako pomocné (operátor), a druhé jako významové:

They do their homework.

Do they do their homework? – první DO je pomocné, za podmětem však následuje ještě jedno jako významové. Věta Do they homework? by byla nesprávná.

How do you do. – tuto otázku všichni určitě znáte.

Některé časy se tvoří s použitím pomocných sloves, která fungují zároveň jako operátory. Přítomný průběhový takto používá sloveso BE (I am sitting – Are you sitting?), předpřítomný čas sloveso HAVE (I have been – Have you been?), předminulý sloveso HAD, budoucí sloveso WILL (I will go – Will you go?) atd. V otázkách tedy pracujeme jen s těmito operátory.

Doplňovací otázky (Wh- questions)

Při tvoření doplňovacích otázek platí všechna výše uvedená pravidla. Rozdíl v těchto větách je v tom, že začínají na tázací zájmeno (Where? When? Who? What? Which? Why? Whose? How? atd.) Vše ostatní je stejné, jako u zjišťovacích (ano/ne) otázek.

He is here. – Where is he?

He likes pizza. – What does he like?

He is 20 years old. – How old is he?

They lost their bag. – What did they lose?

V češtině máme otázky typu: O čem? S kým? Bez koho?. V angličtině však nebývá zvykem umístit předložku před tázací zájmeno (i když by to chyba nebyla), předložka zůstává za slovesem:

They are talking about her. – Who are they talking about?

I went there with my friend. – Who did you go there with?

He is looking at something. – What is he looking at?

Otázka na podmět

Pokud se ptáme na podmět, k převrácení slovosledu (ani používání pomocného DO) nedochází:

Somebody is coming. – Who is coming?

Something happened. – What happened?

Více se o těchto otázkách dočtete v článku Otázky na podmět.

Závěrem

Je toho mnoho, co by šlo ještě doplnit. Existují různé typy otázek, některé se tvoří např. pouhým přidáním otazníku za větu. Svoji zvláštní funkci tvoří také záporné otázky (např. Don't you like that?), doplňující otázky, tázací dovětky atd. To však nebylo předmětem tohoto článku. Záměrem bylo seznámit se základními principy, které by měl každý angličtinář bezpečně znát. Doporučuji neustále tvoření otázek procvičovat. Je totiž nutné, aby se tyto procesy staly automatickými. Nemůžete přece při mluvení stále přemýšlet, co, kde a s čím máte ve větě prohodit.

Homework, October 3rd

Write 13 sentences using the auxiliaries I put on the board. Example:

have - Have you ever met anybody famous? Underline the auxiliary used in the sentence.

auxiliaries: do, does, did, am, is, are, was, were, will, have, has, had, been - have/has/had been

Homework, September 30th

please, in case you still have not done your homework, please watch the following video and

Homework, September 26th

Tomorrow, in class covered by Mr. Kuruc, please do the following job: pick one kind of "writing" from the ones mentioned below, watch the following video and "retell" the story using it.

video link https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cE6OeRZB_Wc

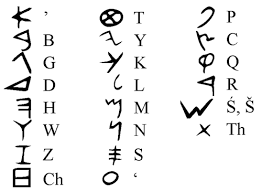

The history of writing/Development of writing

- Cave drawings

- Petroglyphs

- Pictograms

- Ideograms

- Logograms

- Syllabic writing

- Alphabetic writing

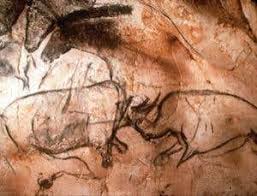

- Cave drawings or paintings – also known as ART ROCK

- The oldest known is located in Chauvet (Šove) Cave, Southern France and is dated to around 30.000 BC (before Christp.n.l.)

- They recorded events

-

- Petroglyphs

- Carvings into a rock surface

- Symbols carved in a rock/stone, wood, or earth

- They date back to 10.000 BC

-

- Pictograms

- Pictures/symbols represented particular (specific) activity, place, concept, object, event by illustration

- They didn’t represent words or sounds in a language

- The difference between a petroglyph and a pictogram:

- A petroglyph simply shows the event, whereas a pictogram tells a story about the event, pictograms were put in chronological order (časovej postupnosti)

-

- Ideograms

- Graphic symbols that represented an idea, a system of „idea writing“

- They didn’t represent words or sounds in a language

- The difference between a pictogram and an ideogram:

- Ο – a pictogram of sun

- Ο – an ideogram of heat, daylight, light, Great God of the Sun

- They were ancestors of Egyptian hieroglyphs and Chinese characters

- Logograms

- A system of word writing (logos – word, from Greek)

- Based on pictographic and ideographic elements

- The earliest known form was made up of RUNES

- Example: cuneiform script used by Sumerians

-

- Syllabic writing

- Also known as syllabary

- Every symbol represents one syllable, e.g. Japanese and Egyptian hieroglyphs

- Alphabetic writing

- Symbols represent single phonemes (grapheme equals phoneme)

- Alphabet – a set of written symbols, a letter – a written symbol

- Alphabets representing manly consonants: Hebrew, Arabic

- Alphabets representing both consonants and vowels: Greek

- Writing systems seem to have gone from syllabaries to alphabets representing mainly consonants to alphabets representing both consonants and vowels.

-

History of Typography for graphic designers and graphic artists

http://planetoftheweb.com/components/promos.php?id=174

Picture writing

The first type of messages that we find in the history records were a series of pictures that told a story known as pictographs.

From pictographs developed more sophisticated ways of communicating through ideographs. Ideographs substituted symbols and abstractions for pictures of events. A symbol of a star represented the heavens or a peace pipe represented peace. Native Americans and Egyptians are examples of some folks who used ideographs. Chinese alphabets are still based on ideographs.

From ideographs developed a system pioneered by the Egyptians known as hieroglyphics. The Egyptians still used drawings to represent objects or ideas, but were the first to use objects to represent sounds.

Letter Development

At around 1200 BC, the Phoenicians gained their independence from the Egyptians and developed their own alphabet that was the first to be composed exclusively of letters.

The Greeks adopted the Phoenician language and began to develop the true beginnings of our modern alphabet. The Greeks refined the Phoenician language by adding the first vowels (5 of them). Their language did not have punctuation, lowercase letters or spaces between words.

The Roman Revolution

The next great civilization, the Romans further developed the alphabet by using 23 letters from the Etruscans who based their language on the Greek. They took the letters ABEZHIKMNOTXY intact, they remodeled the CDGLPRSV and revived two Phoenicians letters discarded by the Greeks, the F and Q. The Z comes at the end of our alphabet because for a while the Romans discarded it, but then brought it back when they thought it was indispensable. The Romans contributed short finishing strokes at the end of letters known as serifs. Roman letters feature the first examples of thick and thin strokes.

Lowercase letters developed because all type was hand copied by scribes who developed less ornate handwriting styles and started using quicker and smaller versions of the letters. The first system of lowercase letterforms was known as the semi-uncial.

The U and W were slowly added and based on the letter V by the year 1000 and the J, which was based on the I was added by 1500. Spacing between words was not generally adopted until the eleventh century. Punctuation marks developed in the 16th century when printing became prevalent.

Miniscules & Printing

Around 732 Charlemagne ordered a system of writing called the Caroline Miniscule which for the first time was the first lowercases that were more than just small versions of uppercase letters.

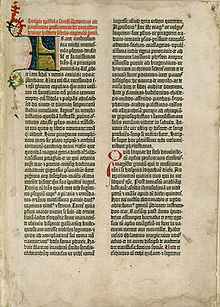

In the 1400's Guttenberg invented a system of moveable type that revolutionized the world and allowed for dramatic mass printing of materials.

In 1500, a printer by the name of Aldus Manutius for the first time invented the concept of pocket or portable books. He also developed the first italic typeface, one of the first typeface variations.

The Type Designers

Claude Garamond from France was the first that developed the first true printing typeface not designed to imitate handwriting, but designed on rigid Geometric principles. Garamond also began the tradition of naming the typeface after himself. Garamond became the dominant typeface for the next 200 years.

In 1557, Robert Granjon invented the first cursive typeface, which was built to simulate handwriting.

In 1734, William Caslon issued the typeface bearing his name which included straighter serifs and greater contrasts between major and minor strokes.

In 1757, John Baskerville introduced the first Transitional Roman which increased contrast between thick and thin strokes, had a nearly vertical stress in the counters and very sharp serifs.

in 1780 Firmin Didot and Giambattista Bodoni of Italy developed the first Modern Romans. The moderns carry the transitionals to the extreme. Thin strokes are hairlines, plus a full vertical stress.

In 1815 Vincent Figgins designed a face with square serifs for the first time and this became known as the Egyptians or more recently as the Slab Serifs.

In 1816 William Caslon IV produced the first typeface without serifs (sans serifs) of any kind, but it was ridiculed at the time.

In the 1920s, Frederic Goudy developed several innovative designs and became the world's first full time type designer. We owe the Broadway typeface to him.

In 1954, Max Miedinger, a Swiss artist created the most popular typeface of our time...Helvetica. The Swiss also championed the use of white space as a design element.

History of Computer Typefaces

The Macintosh

The Macintosh was the first commercially produced computer to showcase the concept of the Graphical User Interface (GUI). It also helped develop the concept of WYSIWYG (What You See is What You Get) printing. What you saw on the screen was similar to what you saw when you printed. The concept was developed at the Xerox Parc research center and pioneered by John Warnock and Chuck Geske, the founders of Adobe, Inc.

Originally, the Macintosh came with ten bitmapped city-named fonts (New York, London, Monaco, Geneva, San Francisco, Venice, Chicago, Los Angeles, Athens, and Cairo). They were wonderful, but have not survived because they were only printable at one size.

Adobe

Adobe invented Postscript which used mathematical calculations to describe typefaces instead of relying on pixel by pixel definitions of fonts.

The original Laserwriter was developed by Adobe in 1985 and came with 13 fonts. It was developed in close association with Apple, and was in fact an Apple branded product, because the first Laserprinter worked only on Macintoshes.

The first 13 fonts were: four variations of Times, Helvetica, Courier and one variation of Symbol. Afterwards, the Laserwriter Plus added 22 fonts for a total of 35 fonts. They included four variations of Times, Avante Garde, Bookman, New Century Schoolbook, Palatino, Courier, Helvetica, and Helvetica Narow. Plus Zapf Chancery Medium, Symbol, and Zapf Dingbats. This was a great group of typefaces which dramatically affected typeface choices for years to come.

For years after that Adobe led the way in developing fonts for personal computers, but Adobe got too greedy. Adobe owned the PostScript language and therefore controlled the way that computers talked to most laserprinters.

The Postscript language supported two different types of fonts. Type 1 and Type 3 postscript fonts. Of the two formats, Type 1 was the more powerful. But Adobe prevented anyone else from developing fonts in the Type 1 format (other vendors were able to develop fonts in the less capable Type 3 format.

The Truetype Revolution

Adobe also developed a version of postscript that could run on personal computer screens called Display PostScript. Adobe offered PostScript to both Apple and Microsoft, but they rejected Adobe's proposal and decided to jointly develop their own font technology called Truetype.

The Truetype format is not as clean and reliable as the type 1 format, but it allowed for an explosion in font design.Unfortunately this explosion caused a large quantity of low quality or designer impostor fonts. Most professional print houses to this day refuse to support Truetype fonts because of their low quality.

The Online Solution

Because of the nature of the online world, you should only specify typefaces in web pages if users have those typefaces installed on their computers. However, it’s impossible to know which typefaces users have on their computers, so this was difficult to do until Microsoft’s Internet Explorer started shipping a set of typefaces with all of their browsers. Since Internet Explorer is by far the leading browser on the web, we call the set of fonts that used to come with IE “Web Safe Fonts”. The list includes: Andale Mono, Arial, Arial Black, Comic Sans, Courier New, Georgia, Impact, Times New Roman, Trebuchet, Verdana and Wingdings.

FONTS

http://www.typography.com/fonts/

Homework, September 24th

learn the punctuation and its usage

Types of Punctuation

The table below lists the types of punctuation used in English. It shows what each punctuation mark looks like and explains its purpose in a sentence.

| Mark |

Symbol |

Purpose |

| Full Stop |

. |

Called a period in the US, the full stop marks the end of a sentence. It suggests a long pause in the writing. |

| Comma |

, |

A comma has two purposes; it can break up a sentence with a short pause between phrases and clauses, or be used to separate items in a list. |

| Question Mark |

? |

This ends a sentence that is a question. |

| Exclamation Mark |

! |

This is a way of showing that the sentence has drama, for example, surprise, anger, annoyance. |

| Colon |

: |

Two uses for a colon. It is used to introduce a list, quotation or, sometimes, speech. Here, it suggests the speech is more important than usual. Or it can be used to show that the second clause in a sentence follows, or explains, the first. |

| Semi Colon |

; |

Again, a semi colon can be used in two ways. It separates items in a list, where each item is made up from several words. More complicatedly, it works to show a pause in a sentence which is greater than a comma, but less than a full stop. This will be where there are two clauses of equal importance next to each other. |

| Apostrophe |

‘ |

There are two, unrelated, apostrophes. The Possessive Apostrophe demonstrates when one noun belongs to another. The Contraction Apostrophe is used to show when letters are missed out. |

| Speech Marks |

“ |

These are used to show when words are either directly said, or directly quoted. Speech marks can be single or double, but frame the spoken or quoted words. |

| Parenthesis |

( )

, ,

—

|

There are three kinds of parentheses – brackets, commas and dashes. These surround extra information in a sentence. |

| Ellipses |

… |

The ellipses have two purposes. Mostly, it is used to indicate a cliff hanger at the end of a sentence. It is also used to show that words have been missed out of a quote or direct speech. |

| Hyphen |

– |

These are used to create a noun made up of two parts. They are gradually diminishing in use. |

More Detail and Examples with Punctuation Marks

-

Full Stop, Question Mark and Exclamation Mark

We cheered on our team at the football stadium.

Who won the game?

They won at last!

These three punctuation marks are, along with the ellipses, sentence enders. A sentence is a unit of meaning. It can be as small as one word (a sentence with special emphasis, for example: The family enjoyed my apple pie. Phew. Here, relief is indicated by the one word ‘Phew.’; with an exclamation mark, surprise would be indicated. A question mark would indicate that the audience has doubt about the outcome. It can be seen that punctuation marks which end sentences are there to help us understand the meaning intended by the writer.

-

Comma

We need to buy apples, flour, sugar and butter to make our apple pie.

In a list, a comma is used to separate each item except for the final two, which are usually separated with the connective ‘and’. However, there is one exception. If the final item in the list is meant to be emphasised, because it carries importance in the sentence, then the Oxford comma is used (before the ‘and’): He visited his parents, his sister, his brother, and his mother in law.

After the match, we went for a drink in the pub.

In normal use, the comma indicates a pause in the sentence. Usually, it separates clauses.

Start your English Learning Online with EF English Live. Sign up today and get a free 14-day trial! Whatever your goals, our online English course guarantees your success.

-

Colon

I heard the commentator say: ‘Goaaaaallll!’

Introducing a quote or speech is a technical use of the colon.

I took my umbrella to the game: I did not want to get wet.

Separating two clauses is for effect, to emphasise meaning. The colon introduces a pause into the sentence, which in turn, adds emphasis to the second half of the sentence.

-

Semi Colon

When we make our ice cream we need: some vanilla pods or essence; a tub of fresh, double cream; some caster sugar; four medium eggs and a pint of milk.

The semi colon is rarely used for emphasis, but adds clarity to a list.

I took my umbrella; the forecast was for rain.

When separating two clauses, because the pause is shorter than for a colon, the second half does not carry additional emphasis.

-

Possessive Apostrophe

My team’s centre forward scored.

How long with the apostrophe last? Its only function is to tell the reader whether the subject of a clause is singular or plural.

-

Contraction Apostrophe

I didn’t expect that!

Again, the apostrophe is for clarity. The use of text speak is beginning to render it redundant. But not yet!

-

Speech Marks (sometimes called quotation marks)

“Yes, yes, yes,” I screamed “It’s there!”

All words AND punctuation that is directly quoted, or said, sits within the speech marks. The only reason for single and double speech marks is to identify speech within speech. For example. “My favourite quote,” said John “is ‘To be or not to be,” from Hamlet.” However, although both forms are correct, they should be used consistently within a particular piece of writing.

-

Parentheses

Johnson (aged 43) is the oldest scorer in the league’s history.

The three forms of parentheses are largely interchangeable. Technically, the brackets simply add information, the dashes add information in a more emotive way and the commas surround a subordinate clause. No native English speaker would object to whichever form the writer chooses.

-

Ellipses

He dribbles, he crosses, the centre forward rises and…

Note…three dots! Not four or two!

The interview was quite long: ‘The boss spoke for ages…we won!’

This use of the ellipses should be for convenience of the reader, and writer, but should not change the meaning of a quote or piece of speech.

-

Hyphen

Thanks to their win, the team’s self-confidence grew.

The hyphen is another mark beginning to become redundant. It is used when two separate words are combined to create a noun. However, a quick look in Word spellchecker shows that increasingly words can be written with or without the hyphen.

Punctuation is a terrific tool. It brings the written word to life and helps to communicate writers’ meanings and intentions. Some pieces have retained their technical use (for example, the semi colon and the apostrophe). Mostly, though, punctuation should be used (sparingly) to help communicate what we want to say.

Homework, September 18th

please, watch the following video about punctuationhttps://www.oxfordonlineenglish.com/english-punctuation-guide

Homework, September 16th

please, revise the facts and figures about Johannes Gutenberg, you are taking a test the very next lesson

September, 13th

- please, learn the vocabulary related to Johannes Gutenberg and get familiar with facts and figures about him

Johannes Gutenberg (1398-1468)

Johannes Gutenberg invented the printing press - the most important invention in modern times.

Without books and computers we wouldn't be able to learn, to pass on information, or to share scientific discoveries. Prior to(before) Gutenberg invented the printing press, making a book was a hard process. It wasn't that hard to write a letter to one person by hand, but to create thousands of books for many people to read was nearly impossible. Without the printing press we wouldn't have had the Scientific Revolution or the Rennaisance. Our world would be very different.

He was born in Mainz, Germany around the year 1398. He was the son of a goldsmith. We do not know much about his childhood. He moved a few times around Germany, but that's all we know for sure.

Inventions

Gutenberg took some existing technologies and some of his own inventions to invent the printing press in the year 1450. One key idea he came up with was moveable type. Rather than use wooden blocks to press ink onto paper, Gutenberg used moveable metal pieces to quickly create pages. He made innovations all the way through the printing process enabling pages to be printed faster. His presses could print thousands of pages per day vs. 40-50 with the old method. This was a dramatic improvement an allowed books to be acquired by the middle class and spread knowledge and education like never before. The invention of the printing press spread rapidly throughout Europe and soon thousands of books were being printed using printing presses.

Among his many contributions to printing are:

- The invention of a process for mass-producing movable type;

- The use of oil-based ink for printing books (farba na olejovom základe)

- Adjustable moulds (nastaviteľné formy)

- Mechanical movable type (mechanická pohyblivá sadzba)

- The use of a wooden printing press similar to the agricultural screw presses (skrutkový lis) of the period

Combination of these elements into a practical system allowed the mass production of printed books.

Gutenberg's method for making type is traditionally considered to have included a type metal alloy (sadzba zhotovená zo zliatiny kovov) and a hand mould (ručná forma) for casting type (odlievanie sadzby). The alloy (zliatina) was a mixture of lead (olova), tin (cínu), and antimony (antimónu) that melted (tavila sa) at a relatively low temperature for faster and more economical casting (odlievanie), cast well (dobre sa odlieval), and created a durable type (a vytvoril trvácnu sadzbu).

First printed books

It is thought that the first printed item using the press was a German poem. Other prints included Latin Grammars and indulgences for the Catholic Church. His real fame came from producing the Gutenberg Bible. It was the first time a Bible was mass-produced and available for anyone outside the church. Bibles were rare and could take up to a year for a priest to transcribe. Gutenberg printed around 200 of these in a relatively short time.

The original Bible was sold for 30 florins. This was a lot of money back then for a commoner, but much, much cheaper than a hand-written version.

There are about 21 complete copies of Gutenberg Bible existing today. One copy is worth about 30 million dollars.

Vocabulary:

Printing press – tlačiarenský stroj invention – vynález

Pass on information – postúpiť, poslať ďalej informáciu

Share scientific discoveries – zdieľať, podeliť sa o vedecké objavy

Prior to – pred, skôr ako invent – vynájsť

Nearly – takmer Scientific Revolution – vedecko-technická revolúcia

Goldsmith – zlatník move – sťahovať sa

For sure – naisto, s istotou key idea –kľúčová/hlavná myšlienka (nápad)

come up with – prísť s čím, vymyslieť moveable type – pohyblivá sadzba

rather than – radšej ako, skôr ako wooden blocks – drevené bloky/kvádre

ink – farba, atrament metal pieces – kovové kusy

all the way through – úplne, v celom enable – umožniť

improvement – zlepšenie allow – dovoliť, povoliť

acquire – získať, dosiahnuť spread – šíriť

knowledge – vedomosti, znalosti education – vzdelanie

mass-produce – masovo vyrábať oil-based ink – farba/atrament na olejovom základe

adjustable – nastaviteľný mould – forma

wooden – drevený similar to – podobný ako

agricultural – poľnohospodársky screw press – skrutkový lis

mass production – masová výroba considered – považovaný

consider – považovať include – zahŕňať

type metal alloy – sadzba zhotovené zo zliatiny kovov alloy – zliatina

hand mould – ručná forma casting type – odlievanie sadzby

type – sadzba mixture – zmes

lead – olovo tin – cín

antimony – antimón melt – taviť sa

low temperature – nízka teplota durable – odolný, trvácny

item – položka, kus German – nemecký

poem – báseň indulgences – odpustky

Catholic Church – katolícka cirkev real – skutočný

Fame – sláva available – dostupný

Rare – vzácny, zriedkavý take up to a year – trvať až rok

Priest – kňaz transcribe – prepísať

Original – pôvodný commoner – bežný človek

Copy – výtlačok worth - hoden

Predprítomný čas (present perfect) – stavba, použitie. Rozdiel predprítomný čas a minulý čas, rozdiel predprítomný čas a prítomný čas jednoduchý. Viac sa dočítate v článku.

Predprítomný čas (present perfect) – stavba, použitie. Rozdiel predprítomný čas a minulý čas, rozdiel predprítomný čas a prítomný čas jednoduchý. Viac sa dočítate v článku.